New clay-based mixture could be the key to smooth sailing on rural roads

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 12/04/2018 (2796 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The cure to Manitoba’s pothole problem may lie in a clay mixture currently being studied and refined at Brandon University.

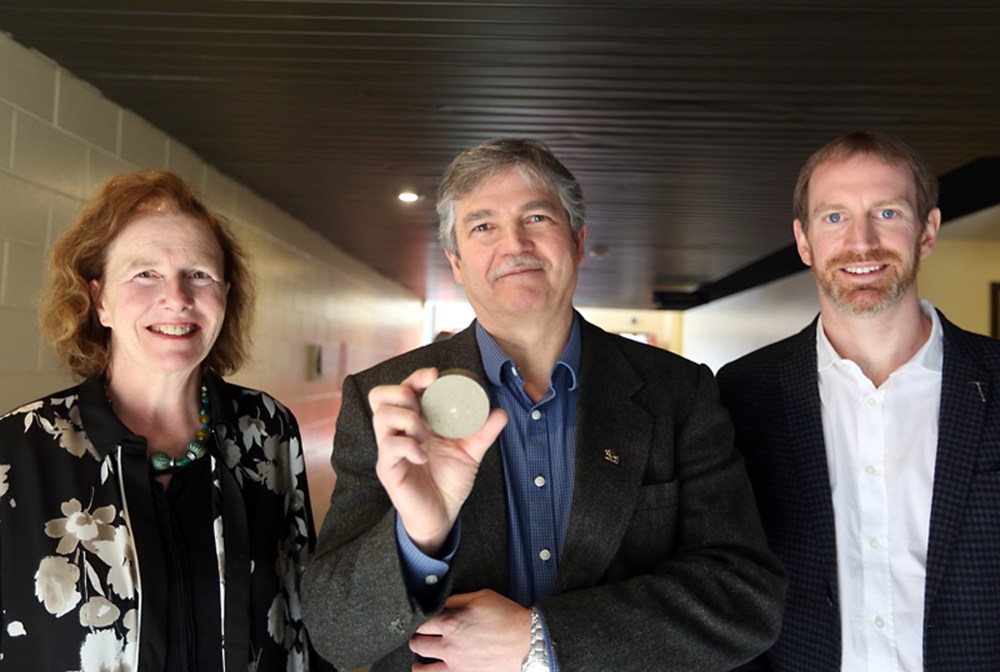

A joint-venture between Dr. Hamid Mumin, a professor of geology at BU, and the Winnipeg-based company Cypher Environmental has shown promising results in creating stable roads that have required little to no maintenance over the past few years.

Speaking to a crowd of municipal leaders, staff and fellow researchers on April 3 in BU’s Louis Riel Room, Mumin explained the science behind the clay-based material and the potential to save money for municipalities in the long run.

“There are a lot of benefits and if there are high-use, high-maintenance roads, the municipalities stand to actually save, in some cases, quite a lot of money,” he said.

Mumin has spent the past four years researching and the testing the material in his lab after meeting Todd Burns, president of Cypher Environmental, at a mining and minerals convention in Winnipeg.

The two talked over the following year and eventually, Mumin decided to study the material further and began seeking municipal partners who could test it on their roads.

Cypher, along with the National Research Council-Industrial Research Assistance Program, helped provide the initial funding and technical support for Mumin’s research.

“So we’re working in tandem with the field tests and the laboratory tests, and to me, for this type of project, that’s what made sense,” Mumin said.

The material, known as EarthZyme, creates a strong glue- or cement-like mixture by replacing water with cations, or molecules that carry a positive electric charge.

Clay carries an excess negative charge, which allows it to bind well to the positive charge held in water.

By replacing water with cations, such as aluminum, magnesium, potassium, sodium and calcium, the clay binds together more strongly.

Using local clay deposits also cuts down on transportation costs, which makes up most of the expenses required to build roads in this manner.

Already, the RM of Cornwallis has had two sections of gravel road, approximately one mile each on Lori and Currie’s Landing Roads, rebuilt using this method.

Reeve Heather Dalgleish said Currie’s Landing, a gravel hauling road, required daily maintenance prior to using the clay mixture, but since 2015, hasn’t required any work at all.

She said Lori Road needed some pothole fixes, but maintenance has been limited to once a year.

“We think there’s a benefit to it,” Dalgleish said. “It’s reducing maintenance need and cost, of course, and allowing us to focus on some of our other roads.”

The cost to build a one-mile stretch of road using the mixture varies depending on the proximity of local clay deposits, but on average, it comes out to $75,000.

“So by utilizing your in situ materials, or higher clay content materials, you’re saving a lot of aggregates that have to be crushed and hauled, and really reducing the frequency at which the road needs to be rebuilt,” Burns said.

“So at the end of the day, there’s a number of different ways you can look at it, but ultimately it’s about minimizing environmental footprint and reducing costs.”

Burns said there are roads that have lasted 10 years or more, with little maintenance, after using this material.

It remains to be seen how long these roads will last in Manitoba, but so far, Mumin said their current test have outperformed expectations.

“This is a far superior way of building those roads. It reduces maintenance costs dramatically, it reduces input costs, almost entirely eliminates any environmental impacts. We foresee that there’s going to be tremendous, widespread use literally across the country and around the world for the technology.”

» mlee@brandonsun.com

» Twitter: @mtaylorlee