BU mum on school of music renaming

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Winnipeg Free Press subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $4.99 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/01/2024 (612 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Brandon University officials are not saying whether a name change is in the works for the conservatory of music and a national music competition after allegations came to light that Ferdinand Eckhardt was a Nazi supporter.

The Eckhardt-Gramatté Conservatory of Music at BU was named after Eckhardt’s wife — musician and composer Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté — during a dedication in 1992.

And an annual national music competition held at BU was also named in her honour in 1976, two years after she died. It’s called the Eckhardt-Gramatté National Music Competition (E-Gré).

A plaque for the Eckhardt-Gramatté Conservatory of Music inside the Queen Elizabeth II Music Building at Brandon University. The conservatory was named in 1992 after Sophie Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté, who is depicted in the photo. (Tim Smith/The Brandon Sun)

In 1970, she received an honorary degree from BU, as did her husband 20 years later.

The Eckhardts were married in Berlin, Germany, in 1934. Nineteen years later, in 1953, they moved to Winnipeg and Eckhardt became director of the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

While conducting research looking into Eckhardt’s life, investigative journalist Conrad Sweatman said he discovered that Eckhardt was a Nazi supporter.

Eckhardt worked for a company in Germany called IG Farben, which was the same company that built the Auschwitz concentration camp and manufactured Zyklon B, the cyanide-based pesticide used in gas chambers, said Sweatman.

“(Eckhardt) leaves behind a bunch of letters and articles that are pledges of loyalty to Hitler that he signed, being made lead art critic of the Reich Chamber of Culture,” said Sweatman.

“He even leaves behind a letter correspondence between him and the militant league for German culture — a Nazi-affiliated outfit that shows he was taking down paintings in galleries because they looked too Jewish. Those were his words.”

Sweatman said he cannot confirm whether there was a direct link to Eckhardt’s wife and Nazism. In reading her journals, he added, she seemed to be more interested in art, and “indifferent to politics.”

But Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté was involved with Eckhardt during his Nazi period, Sweatman said, and that’s reason enough to continue to investigate her life.

“We can hash it out about varying degrees of complicity. But if it’s someone’s principle, or policy, that they don’t have things named after people associated with Nazism, we know she was associated indirectly, and we certainly can’t disprove that she was associated more directly, because it doesn’t seem to me that that research has been done yet,” said Sweatman.

After Sweatman’s article was published in The Walrus, the Winnipeg Art Gallery-Qaumajuq launched an internal investigation. Once it was complete, WAG removed “Eckhardt’s name from the main entrance hall, the website, and all other gallery materials,” wrote WAG-Qaumajuq director and CEO Stephen Borys in a statement on the gallery’s website.

The Queen Elizabeth II Music Building at Brandon University, home to the Eckhardt-Gramatté Conservatory of Music. (Tim Smith/The Brandon Sun)

At Brandon University, Grant Hamilton, director of marketing and communications, said most of the allegations are about Eckhardt, and most of what is at BU is about his wife, and no accusations have been made about her.

“Certainly, we paid attention when the first allegations came forward and lots of people have been talking about it formally and informally,” Hamilton said. “But until there’s a decision, we would keep that discussion ongoing, but not hold it in public.”

In 1990, five years before Eckhardt died, he received an honorary doctorate from Brandon University as Doctor of Laws.

Hamilton said honorary degrees are handled by the Senate office, which is responsible for academic policy and programming, mission and strategy.

“The Senate has an honorary degree committee, and they’d be the ones to decide what happens with any honorary degrees. So, until there’s a decision, I don’t think we would comment,” Hamilton said.

The university has a responsibility to be a leader and a truth seeker and investigate Eckhardt’s wife’s views, said Kelly Saunders, BU political science professor.

Saunders cautioned people against making presumptions that because the husband was a Nazi sympathizer, the wife automatically was. But she added, “This is a very concerning issue.”

“I think as a community, we’re beginning to recognize that there is no time limit for these kinds of views that are fascist, that are racist, that are colonialist,” Saunders said.

“We don’t want to be honouring and marking buildings with these kinds of awful things from the past. We need to atone for that, and certainly that includes remnants of the Nazi fascist era, absolutely.”

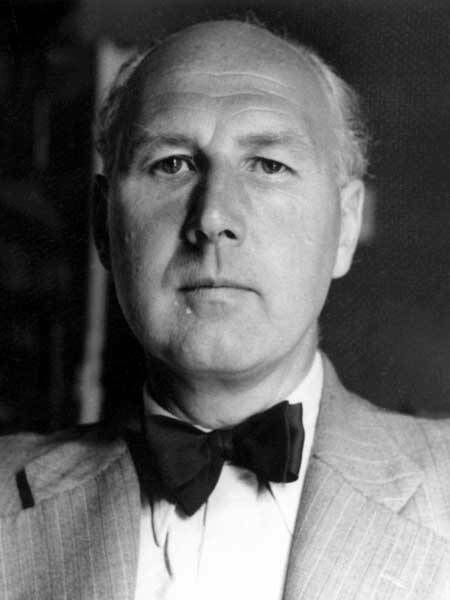

Ferdinand Eckhardt received an honorary degree from Brandon University in 1990. (FIle)

As a public institution, the role of a university is to research, gather data and look at evidence. BU needs to take the initiative and do its homework, Saunders added.

“I’m sure members of the community would be disappointed as well as our alumni and our donors, the community that we’re responsible to. This can have very important and significant consequences, and our reputation as well. So, I think it’s something that I would be very disappointed in this institution, if they didn’t get out in front of this,” Saunders said.

Ferdinand Eckhardt died in 1995 in Winnipeg, at the age of 93.

Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté died in Germany in 1974. She was 75 years old.

» mmcdougall@brandonsun.com

» X: @enviromichele