Rankin’s Universal Winnipeg

Film coloured by filmmaker’s hometown experiences, obsessions

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/01/2025 (316 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

WINNIPEG — Matthew Rankin walked into a downtown Tim Hortons franchise Wednesday, waiting patiently to order his double-double as the crew behind the counter serviced the midday rush at the two-station drive-through.

In true Winnipeg fashion, one lane was closed.

There are no indications of a forthcoming Timmies outpost in Tehran, so as a meeting place for the characters in their acclaimed new film “Universal Language,” director Rankin and co-writers Ila Firouzabadi and Pirouz Nemati dreamed one up instead: a candlelit tea room where old men discuss elusive turkeys in Farsi over the hiss of a samovar.

Symbols of Canadiana, such as Tim Hortons, are reimagined in “Universal Language.” (Oscilloscope Laboratories)

Symbols of Canadiana, such as Tim Hortons, are reimagined in “Universal Language.” (Oscilloscope Laboratories)

When those men order their double-doubles, they receive two hand-poured glasses of black coffee, and they pay for it with currency bearing the face of Louis Riel.

On Wednesday, Rankin’s beverage was what he’d come to expect, and he paid for it with a crisp Wilfrid Laurier.

“Our movie is all about a process of defamiliarization, which should create a new familiarity,” he said.

Released in Winnipeg on Thursday, the same day it narrowly missed an Academy Award nomination for best international film, “Universal Language” is a warmly rendered reflection of identifiable landscapes tilted askew.

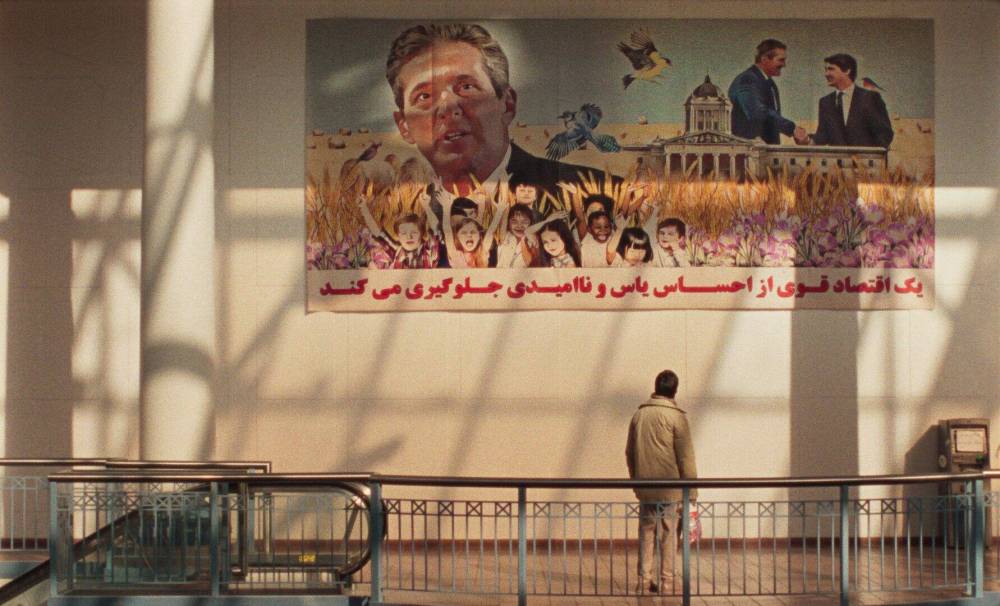

As a surrealist tourist campaign, it presents the city where Rankin was born and raised as a frozen everyland where gamefowl roam free, 10-gallon-hatted pitchmen pervade the airwaves and spiky-haired real estate agents refuse to sleep.

“Winnipeg is a place that continues to exert great pressure on me,” says Rankin, 44, who now lives in Montreal, where the bilingual (French and Farsi) film was shot whenever it wasn’t photographed in Winnipeg.

“Mordecai Richler had this great line about how he moved back to Canada to reconnect with the source of his discontent, so I always want to return to Winnipeg to renew my neurotic affiliations with the city.”

More than any feature film since Guy Maddin’s “My Winnipeg,” “Universal Language” toys with the fallibility of civic memory and international disregard, positioning Winnipeg as both setup and punchline to an absurd joke it writes itself.

“Any movie that takes place in New York will have a joke about New Jersey, and growing up, that might have gone over my head, but I still understood it as an object of condescension. But if you watch a movie in New York City and the Jersey joke gets dispatched, New Yorkers love it. They show up for that Jersey joke in a big way,” he says.

In “Universal Language,” Rankin’s Winnipeg is an in-between city, an artist’s reconsideration of the imperfect, impermanent places that first gave his creative spirit a form.

The film’s lyrical narrative tints Rankin’s own personal lore with detached recognizability. In the opening scene, a teacher trudges through white snow toward a Farsified version of Robert H. Smith School, where Rankin experienced “the first great traumatism of my time.”

Like one of his characters, Rankin — who plays a fictionalized version of his adult self in the film — really did dress up as Groucho Marx for school, wearing a pushbroom moustache and holding a fake cigar.

“My teachers really hated me. A whole fleet of child psychologists were hired to beat this impulse out of me. Still, I spent most of Grade 3 alone in the supply closet dressed as Groucho,” he says.

The film’s schoolhouse sequences are loving homages to Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami’s children’s films; they’re the first indication that “Universal Language” is anything but snide in its treatment of its characters’ aspirations.

Shortly after the bell rings, two sisters uncover a 500-Riel bill frozen under the river’s surface, which kicks off a course of retrieval.

“That story is based on one my grandmother told me to describe her life in the Depression,” he says.

The apocryphal tale reminded him of hallmarks of Iran’s Kanoon Institute, whose films “are always about children facing adult dilemmas and negotiating an adult world.”

“That was very touching to me, that there was this echo between my grandmother, who always lived in Winnipeg, and these Iranian films made on the other side of the world,” says Rankin, who travelled to Iran at 21 years old to visit a film school he discovered had already been shuttered upon his arrival in Tehran, where he remained for three months.

“This was something that enchanted my collaborators Ila Firouzabadi and Pirouz Nemati, the idea of putting these two worlds together into a lobster telephone,” he says of the film, set in a metropolis resembling both Winnipeg and Tehran.

“As absurd as that is, there’s a real idealistic longing to connect and to create a proximity between spaces that typically would be imagined as far apart.”

Though his past film work, including the Winnipeg Jets treatise “Death by Popcorn” and the alt-historical “Twentieth Century,” could be similarly categorized, “Universal Language” is Rankin’s boldest and most vulnerable attempt in his career to confront the impressionist archive of his passionate, shifting nostalgia.

Matthew Rankin plays Matthew in a scene from “Universal Language,” a French and Farsi film that’s set in a metropolis resembling both Winnipeg and Tehran. (Oscilloscope Laboratories)

Matthew Rankin plays Matthew in a scene from “Universal Language,” a French and Farsi film that’s set in a metropolis resembling both Winnipeg and Tehran. (Oscilloscope Laboratories)

Rankin was in Berlin when his mother died in March 2020. He returned home to settle her estate, preparing his childhood home in River Heights for sale in the days of the first COVID lockdown.

“The people who bought it immediately tore it down and built something else,” he says.

Rankin found himself negotiating old, new terrain.

“Alone and wandering through very familiar streets, I found myself lost in them,” he recalls.

“In a lot of ways, the movie did emerge out of a reckoning with the emotional repercussions of the solitude I associate with that period of time.”

It also emerged from the environment Rankin was witnessing through refreshed, grief-stricken and subtly optimistic eyes. In “Universal Language,” the city is divided into colourimetric regions, such as the Beige or Grey districts — areas whose names imply forgetability. But Rankin is a loud advocate of muted tones.

“I’ve long been amazed by Winnipeg’s beige structures,” he says, shortly after stopping at the Lord Rodney, a Sherbrook Street apartment block that’s completely non-descript aside from its brickwork fresco.

“They’ve all been given these very grandiose identities — the Lord Rodney, the Lady Adele, the Lord Hart Manor — but the spaces themselves are completely utilitarian and absolutely failed to provide the grandiosity their identities would suggest.

“There’s something to me about the fall from the sublime to the ridiculous and the divine to the banal that I find very funny, and also very Winnipeg. Winnipeg gets on its high horse and is immediately shot right off of it. I come from a Winnipeg that’s very defiant of all North American mainstream, and I find that that’s true of Winnipeg art in general, but there’s this other Winnipeg that really, really wants to integrate.

“That’s the contrast between Guy Maddin and the Hallmark movement. They’re both expressions of Winnipeg, but very different Winnipegs, and I find that tension really exciting.”

But the filmmaker can relate to the film’s character Massoud (played by Nemati), an enthusiastic tour guide whom Rankin imbued with his late father’s admiration for Winnipeg’s “unrelentingly unloved spaces,” such as spiralling parkades, dormant mall fountains and freeway graveyards.

Rankin insists “Universal Language” — a notably colourful film — wouldn’t look as bright without the gradient of beige apartment buildings such as the Lord Rodney as reflective surfaces.

“I’m not sure which conglomerate controls these buildings, but a lot of them are being painted either grey or black, and I feel that’s such a terrible mistake. There’s a real genius to these buildings being beige, something so beautiful about the way they catch the sun,” he says.

“One thing I love about Winnipeg as a filmmaker is the light. There’s nothing like it. And in the wintertime these beige structures become glowing orbs of warmth. We tried as best as we could to film these beige buildings with the same loving devotion that Terrence Malick films a sunset.”

Rankin never lived in the Lord Rodney — as Massoud notes in the film, nobody notable ever did. But the building now occupies distinct territory in the history of Winnipeg’s filmography, having been seen by audiences everywhere from St. Boniface to Cannes to Tehran, where Rankin’s film had its first “hometown” screening in December.

“I’ve been trying always to document the buildings that fascinate me,” says Rankin, one day before Universal Language premiered in Winnipeg to a sold-out crowd.

“My sincere hope is that the Lord Rodney will become a tourist destination.”

» Winnipeg Free Press