Hospital lawsuit settlement reached

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/03/2025 (238 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A national class-action lawsuit filed more than seven years ago on behalf of former “Indian hospital” patients may have finally been resolved following years of out-of-court negotiations.

Ottawa announced Thursday it has reached a settlement with plaintiffs who filed the class-action lawsuit over their experiences at the hospitals.

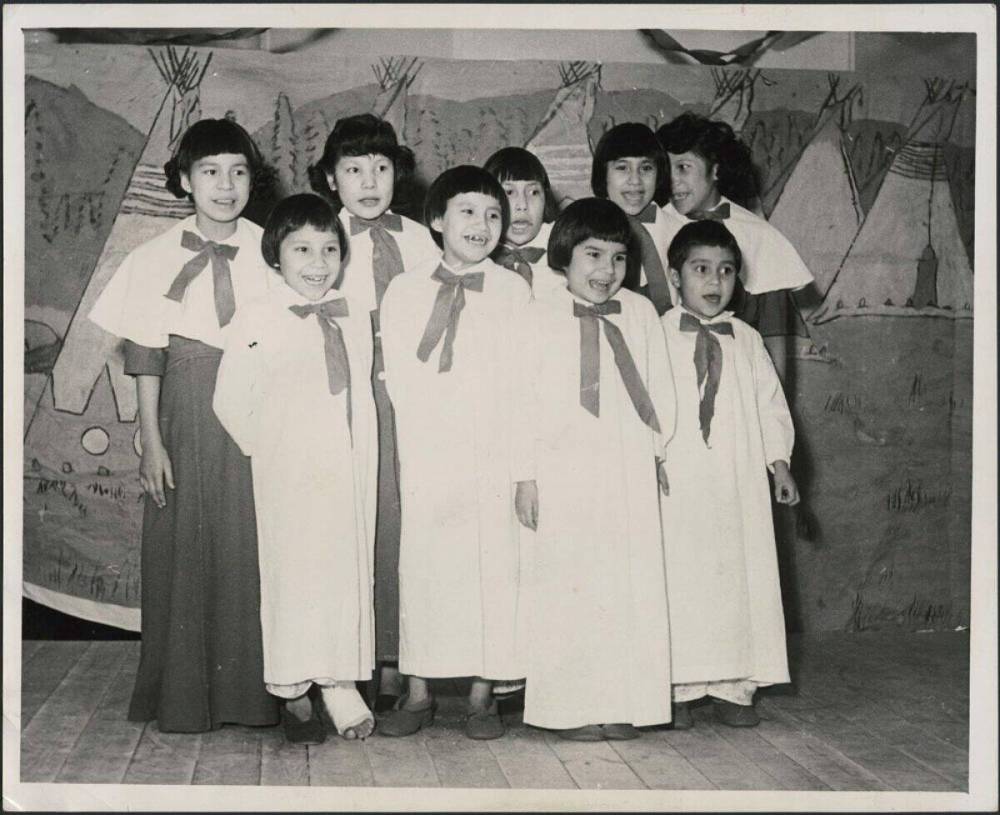

The federal government ran 33 such hospitals between 1936 and 1981, including the Brandon Indian Hospital — also known as the Brandon Sanatorium — which mainly served Indigenous tuberculosis patients from 1947 to 1958.

At the time of its closure, patients were shipped out to the Ninette Sanatorium and the Brandon location was restructured as the Assiniboine Hospital.

Among the list of 29 facilities named in the class-action lawsuit were five other Manitoba Indian Hospitals in addition to the Brandon facility, including the Dynevor Indian Hospital, the Fisher River Indian Hospital, Fort Alexander Indian hospital, Clearwater Lake Indian Hospital and Norway House Indian hospital.

Former patients, some of whom spent years in these segregated facilities, filed a lawsuit against the government in February 2018 alleging the hospitals were rife with abuse and unfair treatment.

“This is something that is terrible, something that’s sort of dragged on this long,” University of Winnipeg historian Mary Jane McCallum said in a conversation with The Brandon Sun on Thursday.

McCallum has been studying Manitoba’s racially segregated tuberculosis treatment facilities over the last several years, collecting the oral histories of former Indian Hospital patients and their families.

She called the settlement an important update for those who experienced racism and assault at these facilities.

“You think of the courage that it takes for people to come forward about this stuff. It’s really hard,” she said. “

The stigma of having tuberculosis is a thing, but also the shame of having been taken away from your family, and then having no one believe you that the hospitals were like this. It’s an amazing thing they’ve done.”

Instead of settling the case through the courts, the federal government and the plaintiffs’ lawyers have been negotiating since 2020.

Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Gary Anandasangaree announced Thursday the federal government has agreed to pay compensation to individual survivors in the range of $10,000 to $200,000.

Ottawa is also earmarking $150 million for a healing fund and $235.5 million for research and education on Indian hospitals.

“I wish this chapter of our history had never happened, but it did. And so we have a responsibility not just to acknowledge it, but to act,” Anandasangaree said Thursday.

“For the survivors who have come forward to share your experience, I want to recognize your courage. It’s not easy to speak about what happened. It’s painful. But your voices have made this possible. They’ve forced your country to listen, to understand and to begin making amends.”

Representative plaintiff Ann Cecile Hardy, a Métis woman who was born in Fort Smith, was just 10 years old when she was admitted to Alberta’s Charles Camsell Indian Hospital. Hardy said the road to the settlement has been a long one.

“It has taken us years of painful reflection, traumatic memories and deep courage to reach this moment,” Hardy said. “I was supposed to be there to heal, but instead I experienced fear, isolation and trauma that has stayed with me for decades … I was repeatedly sexually abused by staff members. I witnessed other patients being sexually abused,” Hardy told those gathered for Thursday’s announcement.

“I left the hospital physically, emotionally, psychologically battered. The abuse I suffered change the entire course of my life.”

Stories like Hardy’s are not uncommon. McCallum says as part of the ongoing work with the Manitoba Indigenous Tuberculosis History Project at the University of Winnipeg, they have heard many stories of people who have had similar experiences.

While she could not perfectly quantify how many people would have been taken to Indian Hospitals in Canada, she said that other researchers estimate that number in the tens of thousands. Among those still alive, most were very young when they were taken to these hospitals.

“We have heard from people we’ve interviewed that when they were children they thought they were being abandoned,” said McCallum, who has listened to both good and bad stories about the hospitals. “We also heard the message that they were very sick and going to these hospitals helped them to recover, and they were grateful about that.”

But McCallum, who has also read many of the hospital records on the subject, says the facilities were always run on a shoestring budget because Indigenous people were not seen as important enough to warrant the extra cost.

“We know what doctors and nurses thought about Indigenous patients, and they believed that they didn’t deserve to, you know, be in hospitals that were as good as those for mainstream Canadians, and that the system should be run at half price. So it’s hard to square those things.”

McCallum said that the Ninette Sanatorium in western Manitoba was not listed as part of this class-action suit because it was not part of the main 33 federally funded facilities. The Sun has also previously reported that, unlike the Brandon Sanatorium, the Ninette Sanatorium was not dedicated exclusively to Indigenous people.

The Federal Court will decide whether to accept the settlement during a hearing on June 10 and 11.

» mgoerzen@brandonsun.com, with files from The Canadian Press