Book Review: ‘Dead Air’ tells history of night Orson Welles unleashed fake Martian invasion

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/11/2024 (406 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Long before Donald Trump used the term “fake news” to complain about coverage he didn’t like, Orson Welles mastered the art of actual fake news.

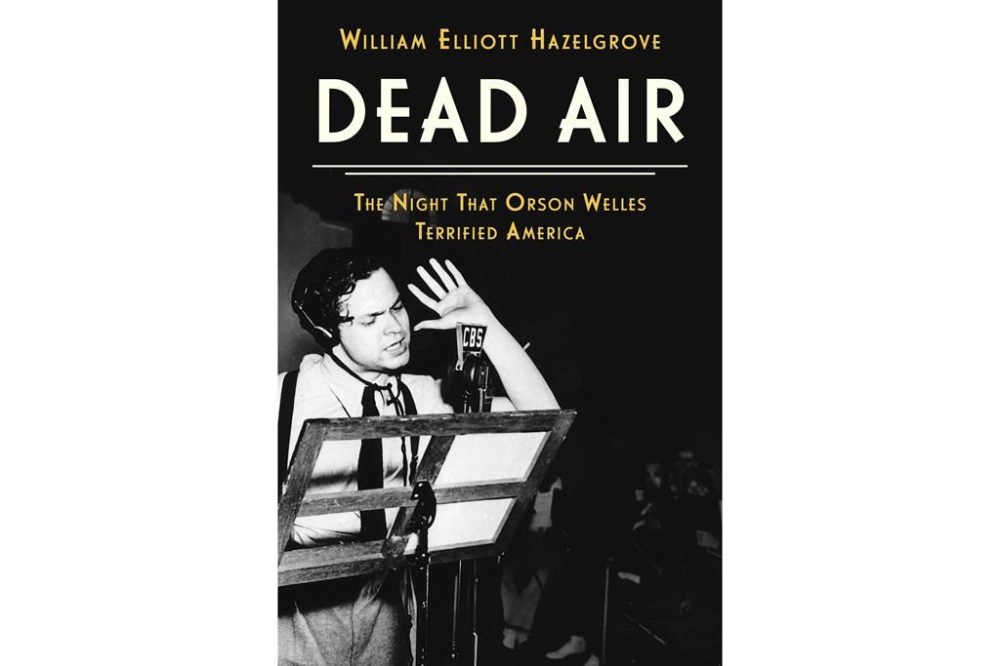

Welles’ 1938 radio adaptation of H.G. Wells’ “The War of the Worlds” is the focus of William Elliott Hazelgrove’s “Dead Air: The Night That Orson Welles Terrified America.”

The book serves as an enjoyable history of the radio drama, with a fair share of fascinating details about its production and historical context. But it falls short on exploring the legendary reports of mass hysteria among listeners who believed they were hearing an actual Martian invasion unfold.

In appropriately cinematic detail, Hazelgrove chronicles Welles’ rise and manic working style — even including a hilarious account of a scuffle that broke out between Welles and Ernest Hemingway and ended with the pair toasting each other over whiskey.

The book highlights what made Welles’ production particularly powerful, airing at a time when millions remained unemployed from the Great Depression and the nation was on edge about the threat of Nazi Germany. He details how Welles took advantage of those fears, including using an actor who sounded like Franklin D. Roosevelt for a part in his broadcast.

“A bottled-up sense of panic was in the air and people could almost smell the fear,” he writes. “Orson Welles would open that bottle and let the fear run wild.”

The book’s biggest flaw is Hazelgrove’s exploration of just how wild that fear ran. Hazelgrove too easily dismisses the modern reappraisal that reports of a widespread panic were exaggerated, and shows little skepticism about news accounts from then that were largely based on anecdotal reports.

Hazelgrove also makes an unconvincing argument that there were deaths that can be attributed to the panic over the broadcast. He even stretches to speculate that a car accident reported on the night of the broadcast could have been related without any evidence to back that up.

There’ no doubt that Welles’ drama had a major impact on pop culture, and “War of the Worlds” will have an enduring legacy. Hazelgrove’s book misses an opportunity to fully revisit the reports of the panic it caused.

___

AP book reviews: https://apnews.com/hub/book-reviews