Remembering Passchendaele 100 years after the battle

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/11/2017 (3002 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The casualty lists were already daunting.

Every day, for the duration of the First World War, the names of Manitoba’s and Canada’s dead and wounded had been published in the pages of The Brandon Daily Sun. Infantrymen killed in action, those who died of wounds, who had been gassed or — still alive — lay wounded in a hospital overseas. Dozens and dozens of family names and initials would line the page, and beside each, a community affected.

Boissevain. Pipestone. Hamiota. Oak River. Winnipeg. Swan Lake. Killarney. Pilot Mound. And, of course, Brandon. And so many others.

But in November 1917, as the Canadians fought in Passchendaele along the Western Front — also known as the Third Battle of Ypres — these lists had become nightmarish. This date, Nov. 10, marks the 100th anniversary of the end of the Battle of Passchendaele, one of the bloodiest episodes of the First World War that ultimately claimed an estimated 487,000 casualties in a mere four months of fighting.

Statistics from the Canadian War Museum state that the British — which included a great number of Canadian battalions — lost an estimated 275,000 casualties at Passchendaele, while the Germans suffered 220,000.

Now a century later, it is from this futile battle that Canadians take our symbols of the horrors of war. As the Canadian War Museum notes on its website, the name Passchendaele has become synonymous with the “terrible and costly fighting” that took place on the Western Front.

The British offensive in Flanders had been launched in the summer of that year, July 31, with the aim of driving the Germans away from essential channel ports, and to eliminate U-Boat bases that were situated along the cost. But days of unyielding rain and shellfire reduced the battlefield “to a vast bog of bodies, water-filled shell craters, and mud,” where continued ground attack had become untenable.

At the time, Canadian troops were still under the auspices of the British. After months of fighting had not moved German troops out of Passchendaele ridge, Sir Douglas Haig, the commander-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force, ordered the Canadians, under Sir Arthur Currie, commander of the Canadian Corps, to attack.

“At this time, the approximate strength of the Canadian Corps itself would have been in and around 100,000 men,” local war historian and retired Canadian Forces soldier Marc George told The Sun. “A lot of British troops, mostly in the form of engineers, artillery and supporting troops were put under the command of the Canadian Corps for the Passchendaele operation, just as they had at Vimy.”

After his lengthy campaign in Flanders, Haig had run out of soldiers to mount an attack. He had exhausted the combat capability of the entire British army, as well as the Australians and the New Zealanders. The Canadian Corps was the last, strong corps that he could commit to take Passchendaele.

“And he is really, in my view, doing this to save his skin,” George said. “He knows full well that if he stops short of Passchendaele, that there’s a tremendous risk that Lord George is going to sack him, because it can easily be portrayed as a defeat. Whereas if he can take the imaginary spot on the ground, then he likely won’t get fired.”

The Canadians land in mid-October to relieve the Australians and New Zealand troops, and are shocked by the conditions that they meet. The small village of Passchendaele was levelled — only rubble remained. The mud was so thick you could literally disappear beneath the surface if you stepped wrongly.

In his book, “Before My Helpless Sight,” author Leo van Bergen wrote the account of Sergeant T. Berry, who watched a man slowly sink at Passchendaele in October 1917.

“He kept begging us to shoot him,” he wrote. “But we couldn’t shoot him. Who could shoot him? We stayed with him, watching him go down in the mud. And he died.”

Van Bergen also retold the account of Frank Richards, who wrote about a route to a casualty clearing station at Passchendaele that was littered with corpses.

“Some were wounded men who had died along the way, or been hit a second time, but there were stretcher-bearers among them … At the end of one battle, six Canadian stretcher-bearers were discovered to be missing. Private F. Hodgson, another Canadian stretcher-bearer, came upon their scattered remains the next day as he made his way to an aid post, where he delivered a wounded man who had died en route.”

Among the most grotesque accounts, George says, was the smell of the Western Front. With the dead piling up within a few square kilometres, van Bergen says that “you could smell the Western Front before you could see it.”

“Most people vomited the first time they ever smelled it,” George said. “It was so terrible. That’s why so many soldiers smoked all the time. The smell of the tobacco helped to mask the smell of all the corruption in the ground. Passchendaele was one of the worst possible battles in that regard, because basically you couldn’t move off of the established tracks or you would sink in the mud and disappear.”

History recounts that the Canadian commander, Currie, launched his “set-piece” attack on Oct. 26, the first of four phases of a battle that he believed could cost the Canadian Corps. upwards of 16,000 killed or wounded. He was eerily accurate — by mid-November, there were 15,654 fallen Canadians.

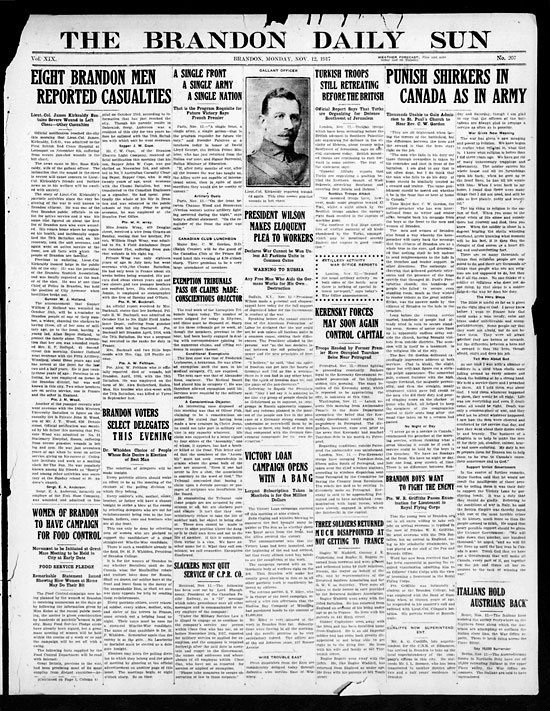

And yet the news at home made it sound either clinical or valiant. On Nov. 10 in the Brandon Sun, a front-page article written by The Associated Press recounted that final battle.

“At sunrise this morning our troops attacked German positions northwest and north of Passchendaele. The first reports indicate that good progress was made.”

Two weeks earlier, an AP story published in the Sun on Oct. 31 reported that it had “been another proud day for Canada,” as the “British reached out across a sea of mud and wrenched away still more of the few remaining defences in the enemy’s Passchendaele system.”

In reality, the Battle of Passchendaele was seen as a failure. So many lives were lost, and so little gain was made against the German lines. Haig’s objective — to reach the coast — was not met.

But the silver lining — if we can call it that — to the horrific experience of the Canadians at Passchendaele, came about from Canadian Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden, whose anger at the tremendous loss of life at Passchendaele prompted him to threaten to send no more troops to the Western Front if such a situation arose again. From this time forward, Canada would be considered an equal among the Allies, and an independent nation of the world.

“It is very much a slim silver lining,” George said. “We would have eventually, without a war, evolved into an independent country. Without question. It’s the way the whole world has gone. If I could pick, I would far rather have had those 16,000 men, not be killed or wounded.”

» mgoerzen@brandonsun.com

» Twitter: @MattGoerzen