Circling back: Sun reporter discovers unique connection to late grandfather

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/03/2022 (1315 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Growing up in British Columbia, the chance of having any kind of connection to Westman seemed unlikely.

My paternal grandparents were both born and raised in the Vancouver area and my maternal grandparents were from Germany and Quebec respectively.

But in the years since I moved to Brandon and my parents started rummaging through some of the old documents my father’s father kept from the Second World War, I discovered Westman was home to a chapter in my grandfather’s life I knew little about.

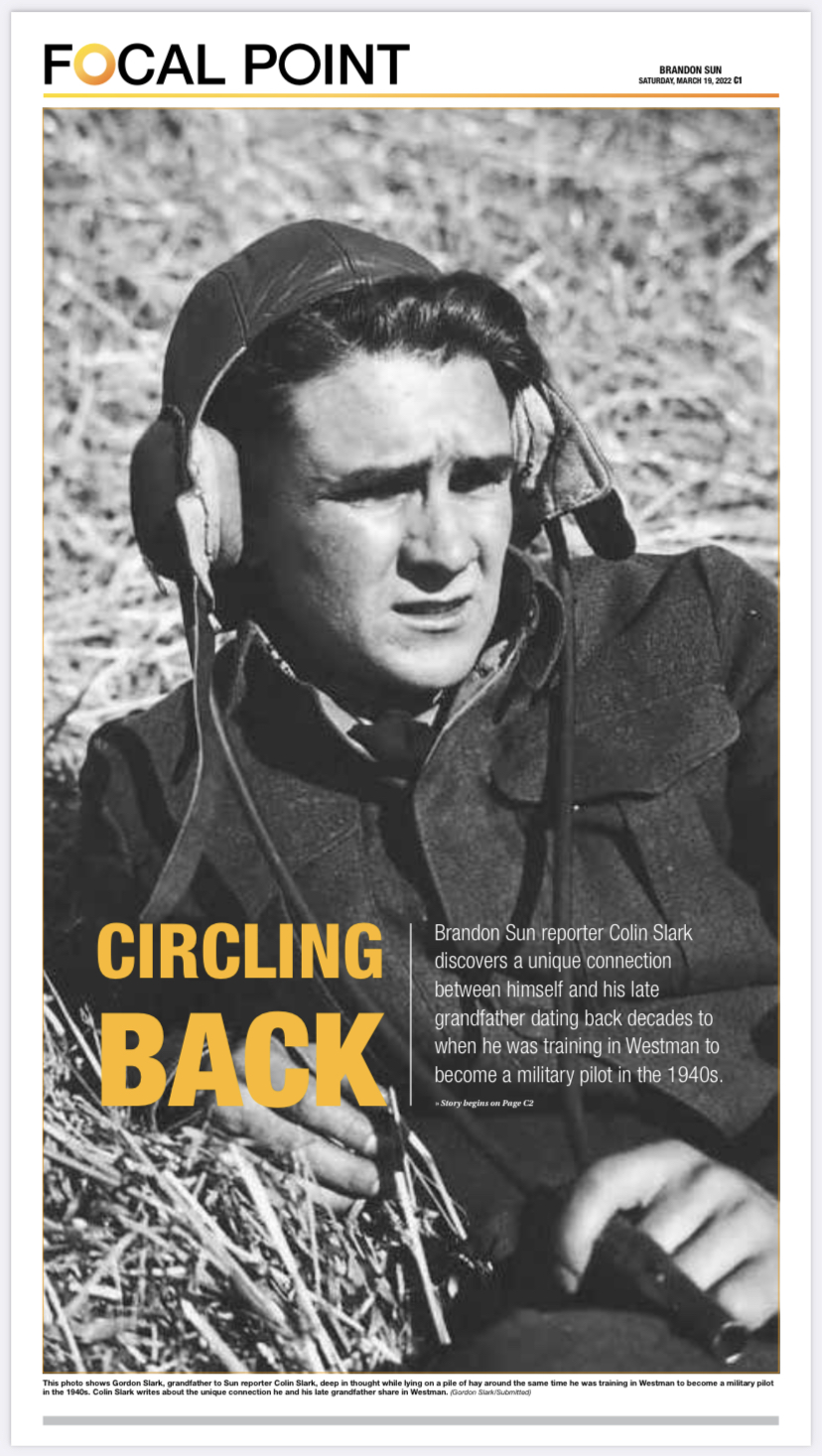

For Gordon Alexander Slark, the man my cousins and I referred to as “Poppa,” military service had been a formative experience and one that left a lasting impression on him and his family in both subtle and noticeable ways.

Though he didn’t tell a lot of stories about the specifics of his service that I can recall, he made sure to attend Remembrance Day ceremonies and other memorial functions in uniform.

One of the medals he proudly wore on his chest, the Burma Star, not only referred to the theatre of war in which he served in India and what is now called Myanmar, but also the brotherhood he maintained with other veterans who served there under an organization with the same name.

The hearing aids he wore were another reminder of his wartime experiences, with the hearing loss worst in his right ear because as co-pilot of a B-24 Liberator, it was closest to the engines on his side of the bomber.

Every morning until he died, he would start the day by doing the calisthenics routine he was taught in the Royal Canadian Air Force, even though his doctors tried to convince him to take it a little easier. But taking it easy was not the kind of person he was.

As his dementia worsened, short- and long-term memory loss would sometimes leave him confused but other times, it would seem as if he could suddenly remember events from long ago as if he were reliving them.

One time I joined him at the kitchen table at his house and he told me something I’d never heard before, an account of one of the battles he participated in.

Though I don’t remember all the details, he did tell the story to a documentary crew working on a short piece about the campaign in Burma called “The Forgotten War.”

In his segment of that documentary, he recalls that the mission wasn’t with his regular crew. He needed flight time and this other bomber was down a co-pilot, so he was brought in as a temporary replacement.

Before the mission, he went for a cup of tea with one of his new comrades from the Canadian Prairies. The other man didn’t have cash on him, so Gordon spotted him with a promise of repayment upon their return.

During a bombing run on Japanese forces, his plane was hit by anti-aircraft fire. Though the plane kept operating, the crew’s navigator was hit in the knee, shattering it.

“I put a tourniquet on it, but he’d lost quite a lot of blood,” my grandfather told the documentary crew. “He was sick, he couldn’t hold his dinner down … I could see he was very pale.”

Trying to return with their dedicated navigator out of commission, the long journey back to base was made even more difficult for my grandfather while he talked to his dying comrade as his life ebbed away.

Hearing this was a shock. I’d heard war stories, but I had no idea that my grandfather had gone through something that painful. I never asked him about any other stories after that, maybe out of fear that I wouldn’t like what I heard, maybe out of concern that it would make him relive events that had scarred him.

In the documentary, my grandfather recalled he had buried the memory until a trip to Regina where the sister of the navigator came up to him and asked him about the incident.

“They never knew,” he said. “They’d never told her. We had a little cry together and that was kind of a nice evening.”

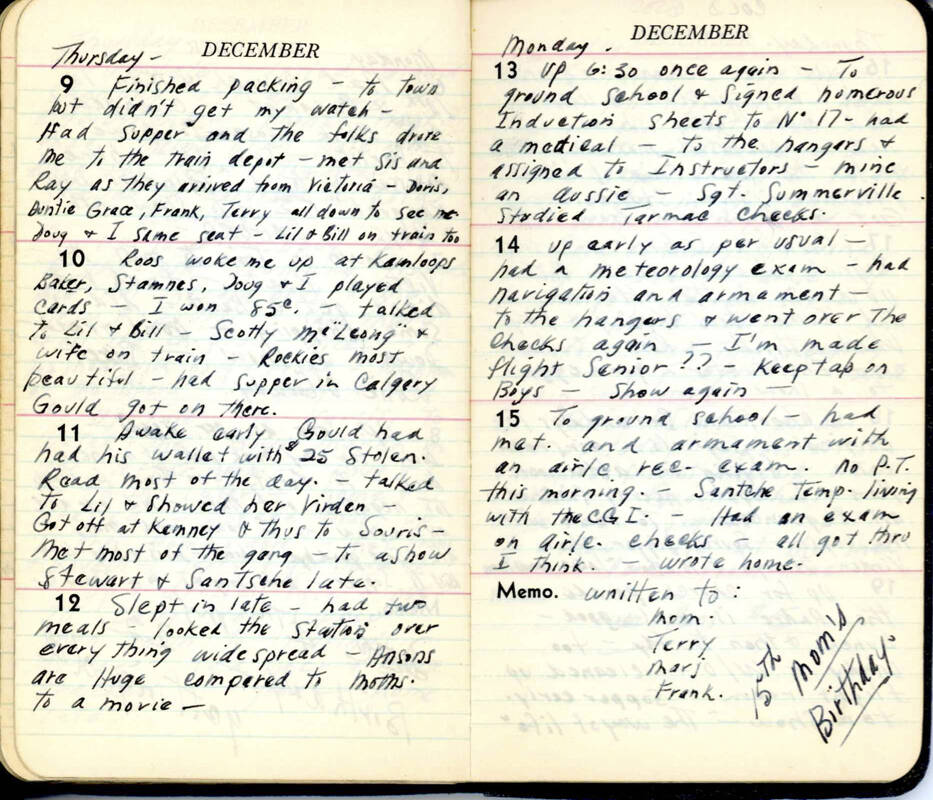

After both of my father’s parents died, there was interest in the stack of journals my grandfather had been writing for most of his life.

I remember in the attempt to sort through two lifetimes’ worth of possessions, I took a look through his 1945 journal. Although the story about the navigator was devastating, there were also moments of laughter like when my grandfather and his compatriots missed the boat heading to England for demobilization after Japan surrendered in August 1945.

After that, I didn’t think much of the journals until after I moved to Brandon in 2019.

One day I received a message from my mother asking me if I’d ever heard of a place called Virden.

Flipping through pages of my grandfather’s journals that covered 1943 through 1945, she had discovered that Gordon received his initial flight training in a small Manitoba community she’d never heard of before.

It was delayed for a while after the COVID-19 pandemic started, but my parents finally managed to make it out to Brandon earlier this year.

On the itinerary was the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum, the only museum dedicated to the effort to train pilots from across the former British Empire in flight schools across Canada to prepare them for aerial combat in the Second World War.

By combining my grandfather’s diaries with the information at the museum, we deepened our understanding of what he went through during the war more than a decade after he died.

On June 17, 1943, Gordon wrote in his diary that he quit his job at the Vancouver Water Board in preparation for enlisting in the Royal Canadian Air Force just six days later.

The day after enlisting, he boarded a train to Edmonton for basic training. Following a good mark on a classification test on July 2, he was on track to be either a pilot, navigator or bomber.

That basic training lasted until early October when he caught a train heading through Moose Jaw, Regina and eventually Virden.

“Arrived Virden about 3 o’clock — to barracks,” his Oct. 3 entry reads. “Very deserted countryside.”

That facility was Elementary Flying Training School No. 19, which taught trainees how to operate De Havilland Tiger Moth and Fairchild Cornell aircraft.

The next day, Gordon was in school for his introduction to airmanship. He learned about the basics of navigation, signals and armament and was assigned to an instructor for 30 minutes in the air in a training aircraft in the afternoon.

While he didn’t get to go up in a plane every day, he clearly enjoyed the experience. On his third day of training in Virden, his journal entry signs off with three words expressing the joy he felt while flying: “Fun no end.”

There was some fun on the ground too, probably a good thing as several days of instruction were cancelled or modified due to weather and cold temperatures.

Thankfully, a friend of his from his days at the University of British Columbia, J.D. McCauley, trained with him in Virden and ended up serving with him in India at the end of their war journeys. My father remembers visits to the McCauley family as a child in the 1960s.

Gordon called Virden “just a village,” but there he saw movies, went bowling and even attended another company’s graduation dance.

“Lots of booze, girls and songs — didn’t drink so not up to scratch,” he wrote on Oct. 13. “Bed 12:30.”

After enviously writing about a comrade named Stewart, who had managed to go for a solo flight the previous week, Gordon finally secured his turn on Oct. 24.

“Up for an hour with Sideen then went up solo for 15 [minutes],” he wrote, underlining solo. “Oh what a thrill.”

Possibly busy with the final training he received in Virden, the entries from Nov. 11 through 24 are completely blank except for one note observing his brother Art’s birthday.

On Nov. 25, it was Gordon’s last full day in Virden. One of Gordon’s photo albums includes the program for the graduation banquet held that night, signed by his fellow graduates.

After packing up, he took a train to Winnipeg the next day where he met with friends, girls and explored Fort Garry. After a few days of fun, he took a train back to Vancouver and arrived in time for his parents’ wedding anniversary.

That vacation ended on Dec. 9, when he hopped on a train to return to Manitoba, getting off at Kemnay and then on to Souris.

The school in Souris was a step up from the one in Virden, teaching those who had passed their first round of instruction. Service Flying Training School No. 17 used Avro Anson and North American Harvard teaching aircraft.

The change in aircraft was not lost on Gordon. “Ansons are huge compared to Moths,” he wrote.

Since the air museum in Brandon has a surviving Tiger Moth, Ansons and even a Harvard, my parents and I were able to see that size difference for ourselves. The Tiger Moth is a single-engine bi-plane while the Anson is a twin-engine multi-role craft.

There were ups and downs. On Dec. 14, Gordon was made flight senior. That diary entry is punctuated by two question marks, as if he wasn’t sure how he’d managed to achieve that. Two days later, he got a talking to at morning inspection for not having his shoes in proper condition.

Coursework included meteorology, navigation and armaments in addition to aircraft practice. Even months into his experience, the novelty of solo flights had not worn off on him.

On Dec. 23, he mentions the Link flight simulator for the first time. Visitors to the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum may have noticed a surviving example of one of these simulators in the historic hangar.

It’s short, cramped and almost looks like some kind of miniature submarine. As my parents and I observed the contraption during our visit, we wondered how it could possibly have been “fun” as my grandfather described. Maybe you had to be there in the moment.

In wartime photo albums my mother recently uncovered, one section shows pictures of Hartney. While there wasn’t a flying school in that community, there was a relief landing field for the Souris school.

Beyond living in the same area in which my grandfather trained in the 1940s, another potential connection between my present and his past shows up in the Dec. 29 edition.

“Receive the paper now — ‘Sun,’” he wrote. Given that the historical Winnipeg Daily Sun had folded by then and the modern Winnipeg Sun wouldn’t launch until 1980, it’s likely he was reading the Brandon Sun — the same paper I work for 80 years later.

After spending the beginning of 1944 in Winnipeg, gaining more flight time and taking some bombing classes, Gordon’s journal for the year abruptly ends on March 5. The next entry we know of is at the beginning of 1945 when he had arrived in India and was preparing to enter combat.

My parents and I aren’t sure if my grandfather became too busy to make diary entries, lost the taste for a while or might have been forbidden to write for fear of divulging military secrets.

The family knows he spent time as a flight instructor in Boundary Bay, B.C. — named because it straddles the border between that province and Washington state — but we weren’t sure of the circumstances.

While we don’t have diary entries for that nine-month period in my grandfather’s life, our visit to the air museum did help us understand why he was sent to be an instructor before combat.

During a conversation with one of the volunteers at the museum, we brought up Gordon’s transfer to Boundary Bay and that we didn’t understand it completely. The volunteer suggested that he must have been recognized for his skills, because that sort of thing happened when the military wanted a pilot to pass on their skills before entering danger.

That theory was confirmed during our exploration of another section of the museum, where that process described in detail on a poster and a plane from the Elementary Flight Training School is included in one of the dioramas.

It’s also likely he spent time there for his final instructions on how to fly B-24 Liberators, as there was also an Operational Training Unit in Boundary Bay.

While the timing isn’t listed, annotations in one of my grandfather’s photo albums show that he travelled to India in a Liberator from Dorval, Que., through Portugal, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt and Iraq before arriving in Karachi, and from there he took a train to Bombay, which is now called Mumbai.

The survival of my grandfather’s war diaries has been a comfort to me since his death, knowing that even though I can no longer ask him questions, I could still learn about a man I dearly loved and respected.

Through taking a job in a city and a region I had never previously visited, I have been able to see some of the same places Gordon did in 1943.

Taking in the museum’s exhibits and artifacts, I saw what kinds of planes in which he trained, learned about the lessons he took and filled in some blanks about what he experienced.

According to Stephen Hayter, the executive director of the Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum, these kinds of family discoveries don’t happen with every visit, but there are still plenty of people who drop by because of their connection to the history encapsulated by the facility.

“We’re just about at the end of being able to talk to [Second World War] veterans personally,” Hayter said. “It’s an opportunity now for families to dig a little deeper into their family’s history.”

While many veterans refuse to discuss their war experiences, some families like mine are fortunate to have journals or logbooks that explain where they went and what they did.

“It’s quite common that family members come to us not knowing the story of their relative in the RCAF,” Hayter said. “It happens frequently that we have families coming through the door with a logbook and want a little interpretation — ‘What [do] these symbols mean, what does this little excerpt refer to?’”

Luckily, Hayter said, the National Archives of Canada holds the service records of those who served in the RCAF. While it takes some time, it can provide a way for families with little information about their loved ones’ service to finally gain some details.

At my grandfather’s funeral, in attendance were those who loved him, those who had enjoyed him as a teacher or principal and a contingent of those who had served with him or who had at least served in the same theatre of war with him.

As the “Last Post” rang out over the hall’s speakers, Gordon’s elderly comrades from the Burma Bombers — even those who could barely walk — marched to the front of the room in their dress uniforms to lay a poppy in front of his portrait and to give a final salute to their brother.

It occurs to me that even though I don’t remember their names more than 10 years after the event, my journey to better understand my grandfather has helped me better understand what they experienced as fellow Commonwealth pilots.

I haven’t always felt like a lucky person, but stumbling my way into a life decision that gave me this kind of insight sure feels like luck to me.

» cslark@brandonsun.com

» Twitter: @ColinSlark