Indigenous woman wants apology for alleged segregation

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/10/2022 (1222 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

An Indigenous woman from Waywayseecappo First Nation who remembers being segregated as a student at Rossburn Elementary School is hoping for an apology from the federal and provincial governments for what she and other First Nation students say they experienced.

Michelle Brandon was six years old when she started attending the school, located 145 kilometres northwest of the city of Brandon, in the 1970s.

Brandon said she, her brother and other First Nations students who attended the school were not allowed to use the front door and were segregated into portable classrooms — called huts — behind the school.

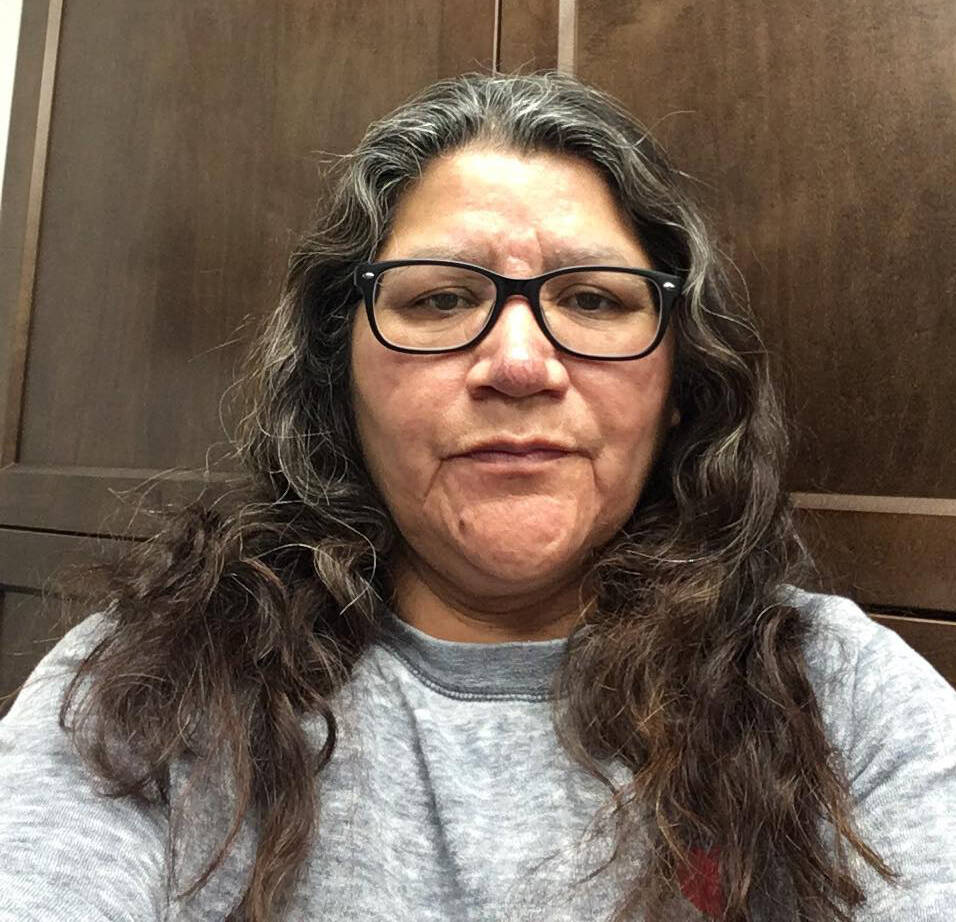

Michelle Brandon says she and other First Nation students were segregated while attending Rossburn Elementary School in the 1970s. (Submitted)

“They ended up separating us and we did not understand it,” Brandon said. “I did not understand, being a little girl, I didn’t understand all that. I thought it was normal for us to be put back there.”

Before 1961, children from Waywayseecappo First Nation, located 151 km northwest of Brandon, attended federally run residential and day schools. After that, the federal government transitioned the students to the provincial school system and schools like Rossburn Elementary, which was run at the time by the Pelly Trail School Division.

Based on the responses the Sun received when it questioned officials about the segregation of Indigenous children at public schools, the apology that Brandon seeks may be tough to secure. The federal government pointed to the province, the province pointed to the school division, and the division superintendent said he didn’t have extensive knowledge of the subject.

Rossburn Elementary School was a provincially run institution, but the federal government provided funding to the Manitoba school board to “support the attendance” of children from Waywayseecappo, according to Jennifer Cooper, spokesperson for Marc Miller, federal minister of Crown-Indigenous relations.

“The resolution of any claim related to the harms suffered by Indigenous students while attending schools that were not federally operated would need to include the provinces, territories and other operators of these institutions,” Cooper told the Sun in an email.

However, according to a provincial spokesperson, school divisions were responsible for the administration of public education and the operation of schools within their boundaries. And portable classrooms have been, and continue to be, used in schools where they are needed to “manage increasing enrolments.”

“Manitoba Education and Early Childhood Learning is not aware of their use for segregation of Indigenous students at Rossburn School,” the spokesperson wrote in an email.

Stephen David, superintendent of Park West School Division, which was established after the merging of the Pelly Trail and Birdtail River school divisions, said he did not have “any extensive knowledge” of the possible segregation of Indigenous students at Rossburn Elementary, owing to the fact that he joined the division in 2002.

“I am not aware of what documents exist, remain or were inherited by Park West School Division from Pelly Trail School Division regarding Rossburn Elementary School in the ’60s and ’70s,” David told the Sun in an email.

Last month’s National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, held on Sept. 30, should have included an apology to Indigenous children who were segregated and abused in the provincial school system, Brandon said.

“I’m hoping to see that it’s being recognized … what happened to us, and that they have to be held accountable, too,” Brandon said of the government.

The experiences First Nations children had while attending schools under the Manitoba school system are being “hidden,” and that needs to change, Brandon said, because Indigenous children still face prejudice in schools across the province today.

“There’s still bullying. My grandkids see it once in a while,” Brandon said. “Bullying needs to be talked about more, it needs to be addressed more.”

Her Rossburn Elementary experience still colours her life today, Brandon said, even though she and other survivors have kept their stories to themselves for years.

“We just want closure, too. Because that’s something we kept with us for so long.”

Remembering her mother’s insistence that she and her brother attend school so they could get an education and create a better life, Brandon said she never told her parents, who had attended residential school, about what was happening at Rossburn.

“We didn’t know how to talk to our parents … and they didn’t know how to communicate with us either, because of what they went through,” Brandon said. “But the love was there. Our parents loved us and that’s what kept us going, because we felt that love from them.”

Despite the segregation she faced in her elementary school years, Brandon said it’s thanks to her parents that she was able to hold fast to the culture of her family and community.

“My parents never lost their culture. We grew up with our sundances … our traditional harvesting of meat and berries, and our language. They kept teaching us as we grew older.”

Today, those traditions continue, with Brandon still living off the land and passing on those teachings to her grandchildren. Another personal triumph over the pain of her past, Brandon said, is that she has finally been able to recognize that what happened to her at school was not her fault.

“I am not a bad person. I am a loving person. I am a caring person. I care for everybody. And for me, that’s my goal — to try and help everybody, because that’s what we need. We need to help each other.”

When the Sun contacted Waywayseecappo First Nation Chief Murray Clearsky, he said he was unable to divulge any information about the issue of segregation of students from his First Nation at the Rossburn Elementary School because it’s currently a topic of discussion with the band council.

» mleybourne@brandonsun.com

» Twitter: @miraleybourne