Growing up queer in Brandon schools

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/05/2023 (887 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

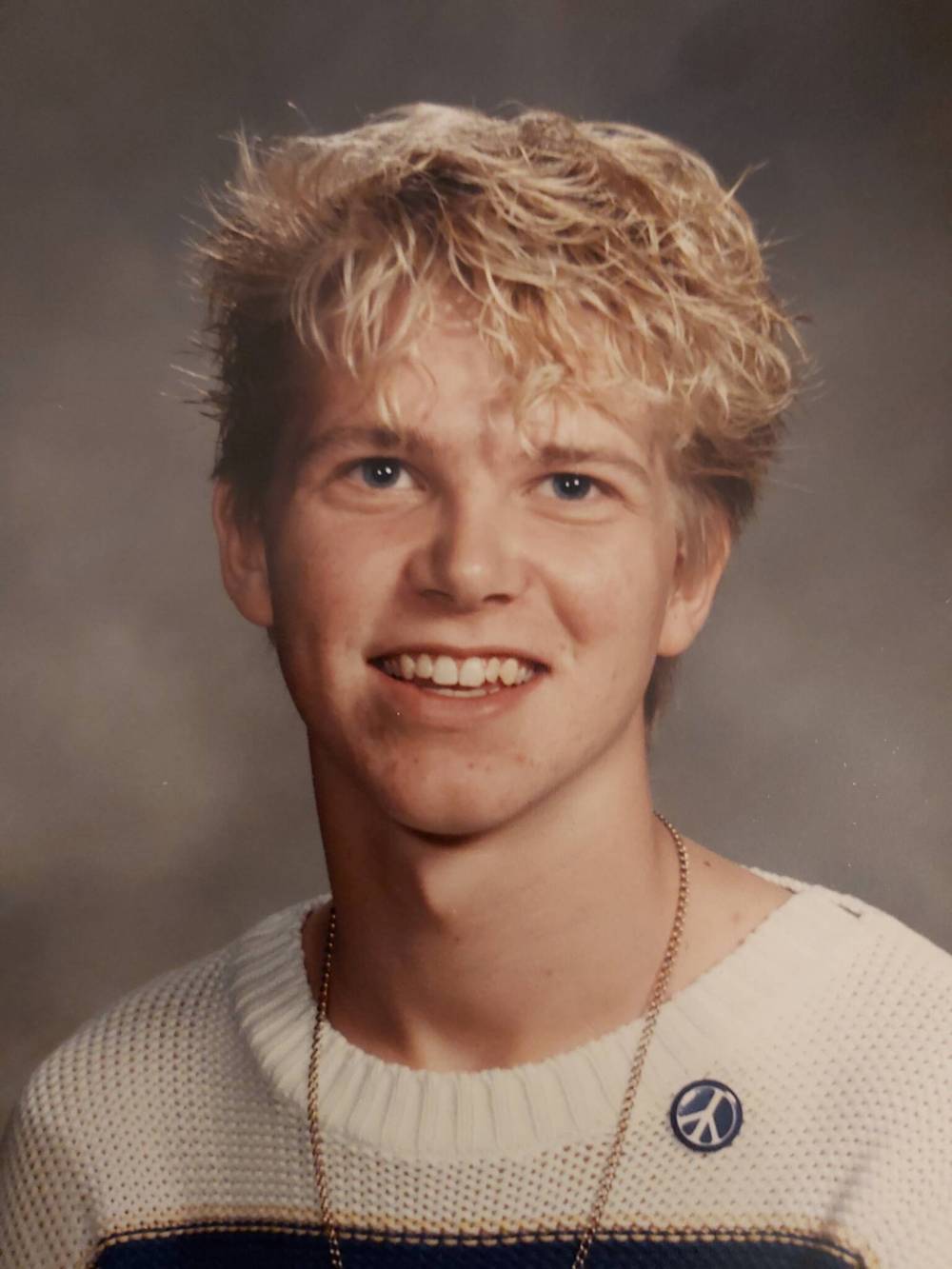

On a visit to Brandon, Allan Tyler saw something so surprising that he pulled his car over to take a picture of it.

Outside Knox United Church at the intersection of Victoria Avenue and 18th Street was a sign commemorating Transgender Day of Remembrance, an annual event memorializing those who have died because of anti-transgender violence.

As a gay man who left Brandon in 1989 because he felt it was a hostile place to grow up queer, Tyler never thought he would see such a sign on display in his hometown.

The sign was a surprise for Tyler, who is now a psychologist working for London South Bank University in the United Kingdom. But, given his experiences as a student in Brandon in the 1970s and ’80s, a recent call to ban books featuring LGBTQ+ topics from schools wasn’t.

At the Brandon School Division’s last board meeting, Lorraine Hackenschmidt — a former trustee of the division in the early ’90s — argued books that discuss subjects like gender identity and sexual health are not appropriate for children to read about.

For Tyler, access to reading material that could have helped him figure out who he was and discover that he was not alone would have been welcome during his years at Meadows School, Crocus Plains Regional Secondary School and Vincent Massey High School.

“There are kids who get bullied and there are kids who are different but are still part of an easy social scene,” Tyler said. “Being the queer kid wasn’t the only thing that made me different. I was a weird kid. I kind of marched to my own drummer but, if I’m being fair to the kids I went to school with, I didn’t have the same set of social skills.”

Although Tyler said he did his best to turn the other cheek until both were red and raw, the bullying inflicted on him escalated from name calling to death threats over the phone.

Callers said they would drive Tyler’s new car off the road and hurt him. This, he said, was the decade before 21-year-old University of Wyoming student Matthew Shepard was brutally beaten to death in 1998.

At a bar in Laramie, Wy., two men offered Shepard a ride home. They drove out to a rural area, robbed and tortured him, tied him to a barbed-wire fence and left him to die. Shepard was eventually discovered and taken to a Colorado hospital but succumbed to his injuries days later.

Tyler recorded one of these calls and took it to his school’s vice-principal. At the time, Cyndi Lauper was his musical idol. He recalled wearing plaid jeans, an Army/Navy jacket, a T-shirt with a design he printed on himself, and he sported an asymmetrical haircut that was shaved on one side and long on the other.

He said the vice-principal’s response was that the cause of the bullying was likely that Tyler dressed differently than the other kids, drawing attention to himself.

“The message from him was ‘be less different, stand out less and you’ll be fine,’” Tyler said. “And I said, it’s not that, I’ve tried the Levi’s jeans and the Benetton sweatshirt, so why bother trying?”

Unsatisfied with the vice-principal’s answer, Tyler threatened to contact police if the school didn’t deal with the issue. He said he never heard about the issue again from the vice-principal, but the classmates he’d accused were eventually marched into the principal’s office and the threats stopped.

Tyler said that at the time, he had the thoughts and feelings of a person working on discovering themselves, but he wasn’t “out” to himself, let alone anyone else. But he was noticeably different.

“The idea of ‘sexualizing children’ is a challenge to talk about,” Tyler said. “Kids don’t just hit 18 and suddenly have fully formed adult identities with the thoughts and the feelings and the crushes. I had a poster of Wonder Woman on my bedroom wall, and it was never about being attracted to Wonder Woman. I wanted to be Wonder Woman.”

At the time, he wasn’t out to anyone, not even to himself. He had never been asked if he was gay. However, he’s not sure his sexuality was necessarily a secret.

He didn’t want to say definitively that there weren’t any books discussing LGBTQ+ topics in his school libraries as a child, but he can’t remember any.

Being openly gay back then wasn’t possible due to the stigma, he said. But disinformation around the LGBTQ+ community persists today.

Hackenschmidt’s presentation, for instance, suggested that access to queer content is setting up children to be victims of sexual grooming or pedophilia.

In a letter Tyler sent to the Sun, Brandon Pride and other organizations in response to Hackenschmidt’s presentation, he criticizes, among other things, the assertion that some materials should be removed from the access of innocent minds before their brains mature.

He points out that research has shown that areas where access to information on topics like birth control, sexually transmitted infections, sex before marriage, consent, sexual assault and incest is limited have higher rates of teenage pregnancy, unreported sexual assaults and untreated illnesses.

“In primary school, we were read Bible stories, but I’ve never owned a slave, had multiple wives, or prepared to sacrifice my son on an altar. I never thought cutting a baby in half was a serious solution to a custody struggle,” he wrote in the letter.

On top of Tyler’s work as a psychologist and academic where he has written about LGBTQ+ mental health in England, he also collaborates with the Croydon Safeguarding Children Partnership, a group in the south of England that educates and supports workers like teachers, emergency responders and mental health professionals tackle queer issues.

Six years ago, then-Grade 11 nonbinary student Navan Forsythe, who uses they/them pronouns, went before the Brandon school board with a request to make local schools more inclusive for LGBTQ+ students.

Specifically, Forsythe wanted more gender-inclusive washrooms and for division staff to receive ally training to understand issues raised by queer students. Generally, such training teaches adults to be an ally to LGBTQ+ youth by educating them about terminology and the challenges nonbinary youth face.

Speaking to the Sun from Edmonton, Forsythe said that when they were a student in Brandon, there was only one gender-neutral stall for all transgender students to use at the school. And while ally training was available for staff, it was not mandatory, they said. Forsythe said their concerns weren’t followed up by the division.

After hearing about Hackenschmidt’s presentation, Forsythe watched the archived video on the school division’s website.

“I did not enjoy watching it,” Forsythe said. “But I felt that I needed to know more … I was genuinely worried because of how much support she seemed to get, both from the outwards thanks she received and the complete and total silence from the remainder of the board.”

A couple of the books cited by Hackenschmidt — “Being Jazz” by Jazz Jennings and “Rethinking Normal” by Katie Rain Hill — are written by transgender women and discuss their respective transitions.

Forsythe doesn’t remember books like those while they were in school.

“There were some things relating to sexuality, there may have been books relating to sex education … but on gender identity there were not.”

At the time, Forsythe was familiar with the story of Jazz Jennings because she was another transgender person around their age, but added they would’ve appreciated having more diverse literature at school.

“I had to at that time just kind of figure it out. Knowing there was more of a community and knowing that these were paths people had [tried] before sooner would have been helpful to me and my queer and trans classmates at the time.”

JD Crookshanks has heard about the recent presentation to the school board but doesn’t want to watch it.

“I don’t want to go through that, having to listen to someone say all these lies about the LGBTQ community,” he said. “I’ve lived through that.”

He graduated from École Neelin High School in 1997 but didn’t come out as gay until almost the end of his time in public schools.

“The ’80s were especially bad because of the paranoia and myths around HIV and the pervasive libel around LGBT people being pedophiles and grooming people,” Crookshanks said. “I’d like to think it’s believed less now, and it probably is … but there are still some people who perpetuate that lie.”

The ’90s, he said, were marginally better because positive examples of gay and lesbian people started to appear on television — though he notes there weren’t many, if any, positive depictions of trans people then.

“It would have been nice to have had resources available to let me know that I wasn’t alone and there was nothing inherently wrong with me,” he said. “All we had was the very start of the internet and that wasn’t a great resource at all. If you’re worried about kids seeing pornography, I don’t know why you’d drive them onto the internet by taking books out of schools.”

Not only are such resources helpful for queer students, Crookshanks said, but they offer positive depictions of LGBTQ+ people to cisgender and heterosexual students.

Kent Ranson, a medical doctor and health economist with the World Bank in Switzerland, said he “came out almost the minute I moved away from Brandon.”

He attended Brandon public schools in the ’70s and ’80s, before graduating with a science degree from Brandon University in the early ’90s.

Unlike Tyler, Ranson said he didn’t necessarily feel like Brandon was a dangerous or unsafe space, but he knew of queer people in the city who lived lonely or isolated lives. He said he wanted to live somewhere with a community of gay, lesbian and other friends.

“At the age of 21, I wanted to go to places where I could at least experience that,” he said. “I knew I didn’t want to live the rest of my life as sort of an independent gay man without much community in Brandon.”

During his childhood, he said there was no internet and no access to reading material featuring LGBTQ+ people, but more examples of gay people were shown on television programs like the “Oprah Winfrey Show.”

“For the first time, I began to get glimpses of what gay life and gay role models look like,” he said.

Before that, the emergence of the HIV/AIDS crisis in the ’80s through health-care facilities and on television discussed the potential health risks of being a sexually active gay man. The mortality rate among gay men was frightening, but so was the public’s view of HIV as a disease that only or mostly affected gay people.

After he moved to Ontario for medical school, the first place he went in Toronto was the Glad Day Bookshop, which states on its website it is the oldest queer bookstore in the world.

“I had never imagined there would be an entire bookstore with nothing but gay literature,” he said. “Then I started to buy all sorts of books that were fiction, but fiction about gay and lesbian and queer relationships and families. It was great for me to be able to access that.”

Two years ago, Tyler received an unexpected message on social media from a former classmate. The man apologized for how he and his peers had treated Tyler and expressed regret that they hadn’t received any education about gay people. If they had, they would have known there was nothing wrong with being gay.

At first, Tyler said it didn’t feel safe to receive the note.

“Who the hell is this, reaching out after all these years, and what does he want?” he said. “That’s part of a trauma response.

“It probably was a year later when I fully relaxed into [thinking], ‘this is an authentic apology’ … as the conversation continued, I could realize it was a genuine expression of regret.”

While crafting his letter in response to Hackenschmidt’s presentation, the note from his former classmate struck him differently.

“When I re-read it as part of sending this letter, it touched me in a very different way to see this was the direction of travel for this person, here’s the journey he’s been on. Sure, it took 30 years, but it’s amazing he got there because some people never do.”

» cslark@brandonsun.com

» Twitter: @ColinSlark