Ferguson’s legacy measured in grads over goals Brandon University alumni series

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/10/2021 (1595 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

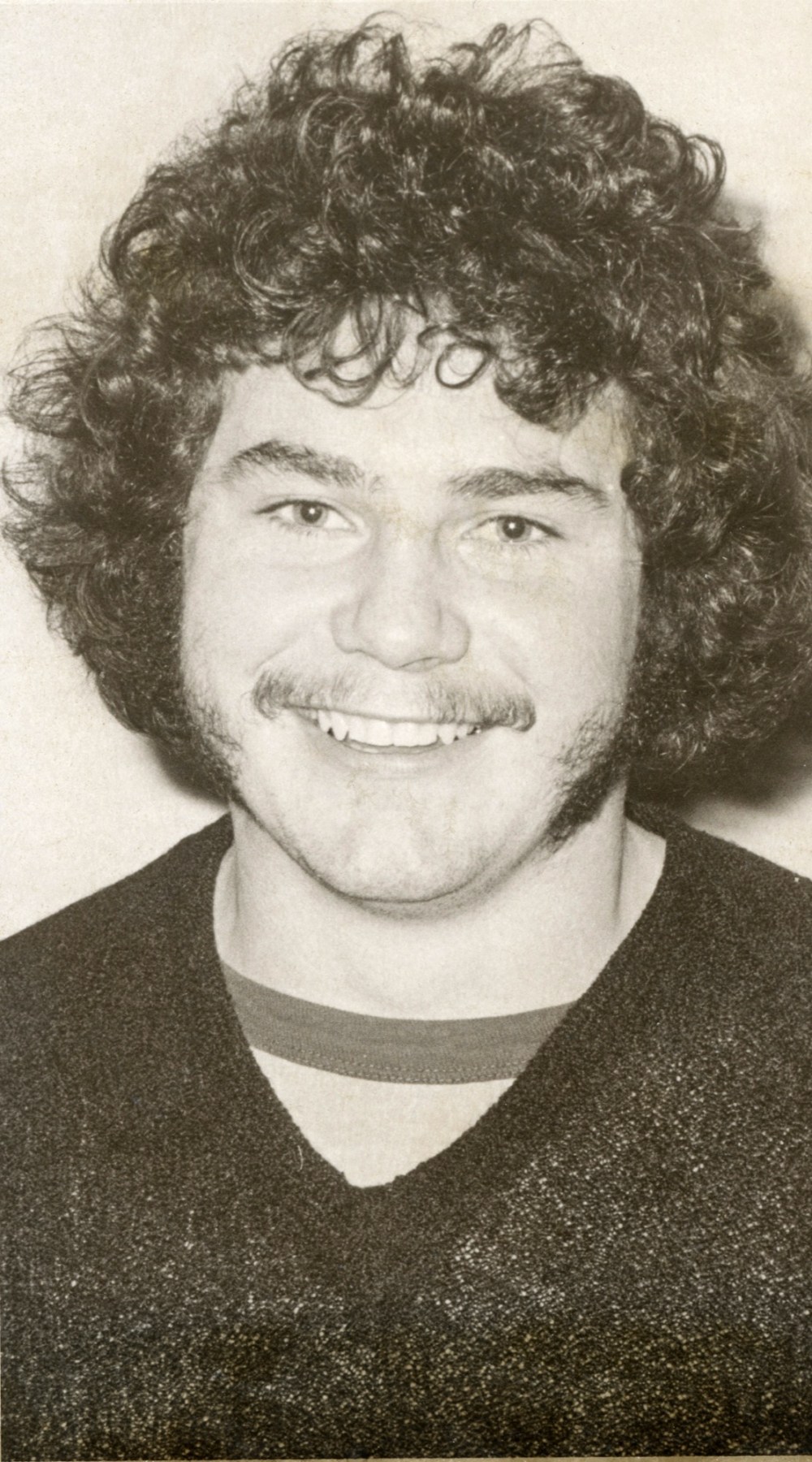

Jim Ferguson slept in his hockey equipment the night before his first game.

That is, if you can even call it equipment. A pair of old bamboo gloves, some felt pads, two pieces of plastic strapped together to form a helmet, skates far too loose and pants a few sizes too small were all he could muster together at age 10.

“I didn’t care. It was the neatest thing,” Ferguson said. “My dad (Malcolm) gave me the bag he used to carry his equipment when he got out of the army. So he emptied that all out, I put all my stuff in there, he bought me a stick for a couple of bucks and I was good to go.”

Ferguson’s parents had just divorced that year and he lived at his mother’s place on 26th Street. It was actually the man his mom, Shirley Matheson, started seeing that got him into the game. In 1965, he dragged Ferguson down to a bean feed, where for five bucks they could eat, listen to Detroit Red Wings great Gordie Howe speak and register for minor hockey.

Ferguson’s Saturday morning games started at 7 o’clock, 16 blocks away at the old Wheat City Arena on 10th and Victoria, where the Brandon Police Service station currently sits.

The odd time he had two nickels to rub together, he’d catch a bus. Otherwise, he walked.

“I’d get up about 5:30 … just couldn’t care less that I was cold. Then you got in the arena and it was just the neatest thing seeing all these big guys play,” Ferguson said. “In my first year I didn’t see a lot of ice time and I didn’t really care, till towards the end of the year.”

Seven years later, Ferguson was once again astounded at the big guys playing alongside him. This time, however, it was as a Brandon University Bobcat rookie. He spent four years with the team, winning two Great Plains Athletic Conference titles while studying to become an educator and a guidance counsellor, then one of the first teachers with the Neelin High School Off Campus program in 2007.

Now 67, Ferguson looks back on a career much like his time on the ice. It’s measured not in personal accolades and achievements but lives changed for the better, in large part because of his humble roots, willingness to face great challenges head-on and undeniable ability to bring the best out of people who didn’t fit the typical mould of a successful student.

Hockey certainly helped shape who Ferguson is today, and something had to really help him sink his teeth into the sport. That moment came halfway through his first season, immediately following a penalty he took.

“I’m sure what happened is I fell in front of somebody and tripped them,” he said with a chuckle, adding his oversized skates had him going over on his ankles often.

“But I jumped out of the box and … the coach yells ‘Go, go,’ so I jumped in to their end, the shot came from the point and there I was in front of the net. I took a swing at it and somehow it just made it in.

“It was exciting, Oh man, I scored a goal even though I didn’t know how. Wow, was it great. That’s my big memory of my first year … After that I was hooked. I had to play. I had to keep playing.”

Ferguson continued to grind away each season, never one of the best players around town, not picked for an all-star team until age 15. While he upgraded what equipment he could, he didn’t have the gear or the game to stand out, but that started to change.

In his lone season of midget, he got a special upgrade.

“I had (Bauer) Black Panther skates at 15. A sheet of paper had more strength in the walls than they did. My friend, who was an amazing defenceman Laurie De Roo … Laurie wore (CCM) Tacks. Anybody who was anybody wore Tacks,” Ferguson recalled. “He’s getting a new pair of Tacks and says ‘Hey, I’ll sell you my old ones for five bucks.’

“Right size, but the front part, the leather underneath … was worn out so the skate blade part on the toe was loose, it was almost falling out. What do you do? I took an extra skate lace and I tied it up and I played the rest of the year … with my skate lace tied up, tied my boot to the blade.

“I know that sounds really stupid, but I had Tacks on.”

Ferguson recalls the all-star squad that year, which would travel outside the city unlike house league teams, was thin on the blue-line. He earned a spot as the fifth defenceman.

“It was a great, great experience that sold me on hockey. A lot of the guys I played with went on to play junior hockey,” Ferguson said.

He played juvenile for coach Jim Mann the following year. Ferguson said Mann, who previously coached the Bobcats, got everything out of him and took his game to the next level. He recalls a weekend he had a basketball city final with his Neelin Spartans that conflicted with hockey provincials in The Pas. Mann helped him get a bus ticket so he could hit the court then jump on an overnight bus to help the team capture a provincial title.

BU coach Wayne Davies saw him play earlier that season in Virden and asked him to try out for the Bobcats in 1972.

Ferguson considered Junior A hockey and attended Selkirk Steelers camp in August but realized the game might have been a little too big for his five-foot-eight frame.

He figured the university schedule with four practices and two games a week was perfect.

Now he humbly states that he wouldn’t have made the team at all if not for good timing. A veteran group, including Bruce Bonk and Jack Borotsik, had moved on and his rookie class was a large one.

Even so, he was a 17-year-old standing shoulder-to-torso with talented junior guys much older and stronger.

“Real, real quick I got my eyes opened. University hockey was very fast,” Ferguson said.

“… I had to work really hard. The guys I respected on the team, there was Doug Gillies… Doug was an amazing defenceman. Brian Boyle from Moose Jaw, same thing, Clark Lang, played with the Wheat Kings, Larry Budzinski, our goaltender who was an amazing guy … I would do anything for them. If somebody was going to fight one of my guys, I was in there. It’s kind of hard to explain but hockey became my identity and yet I had a lot of work to do.”

Brandon finished ahead of the University of Manitoba to avoid last place in the conference that year. Following a coaching change to Bob Kabel, the Bobcats captured their first GPAC title in 1974. They were ranked sixth in the country and came agonizingly close to the national final four.

“We were down 2-1 and Perry Robinson, who if not the best forward, one of the best forwards ever at BU, he was excellent. Few seconds left, I can see him rushing to the point, tips the puck past their guy, goes the length of the ice … top corner, right up top, bulged the twine and that tied it two-all,” said Ferguson, who was on the ice a full extra frame and change later when it all ended.

“We went down and Greg Thompson fired a slap shot that hit the post. They came down and scored, in double overtime … It was heartbreaking. Heartbreaking but redeeming in a sense.”

BU defended its GPAC title in 1975, that time losing to Canada West champ Alberta for the nationals trip.

The Bobcats came up short of the three-peat in 1976, and while Ferguson figures he never scored more than a few goals a season, he looks back fondly on those four years.

Heck, he was simply stunned at the fact that the school provided hockey sticks for the players.

“For me personally, I never ever thought I would ever play for a team like BU so when I got there I cherished it. I couldn’t believe these guys really thought I was capable of playing with them. I wanted to do everything I could for them,” Ferguson said.

“I couldn’t score, all I could do was hit and by my last year I wasn’t a pretty skater but I was as fast as most. We faced so many tough challenges. We went out to play against UBC my second year and they were ranked No. 1 in Canada. We lost 4-3, 3-2. The stands were full, probably maybe 4,000 people.

“I was in awe, in awe, that I would get to do that. I guess I always look back at it like it really helped me to grow … being in pressure situations, killing penalties … fighting for my teammates, just (gave me) such confidence.”

That confidence truly came with practice, and from moments like the one fight with a University of Manitoba Bison that he won’t forget. The guy threw a punch when they were battling against the boards so Ferguson whacked him back with his stick. When he skated away, the Bison chased him.

“I think he was seven-foot-eight and I was five-foot-eight,” said Ferguson, who played at south of 200 pounds.

“His first punch put my tooth through my lip and I knew ‘OK, this is it unless you pull it together.’ Something kicked in and all of a sudden I wasn’t afraid anymore … We wrestled. He was about six inches on my length so … I had to grab him, pull him in and try to punch up.”

Ferguson said his newly acquired fearlessness caused him to tread in places he maybe shouldn’t have later on, but it also lead to a decision that may have saved more than a few people.

There were a few stops before that run-in, though, so stay tuned.

While the Bobcats came up shy of a GPAC title in 1976, Ferguson still ended up with a ring that year. He met his now wife Shelley (nee Wark) halfway through the 1975-76 season.

“We clicked and within a month I asked her to marry me. We set the time for that summer,” Ferguson said. “Not saying I’d recommend it that way but it worked for me.”

Ferguson didn’t land a teaching position that year, picking up a few odd manual-labour jobs to make ends meet. Throwing bales, painting a basement, he took whatever he could get. He admitted it was tough at 21, feeling like he was having trouble supporting his wife.

When he still found himself without a teaching position in 1977, he interviewed for one in Snow Lake, 800 kilometres north of Brandon. Ferguson taught Grade 6 that year, then spent two teaching Grade 9 and 10 math and science. By the time Jim and Shelley returned to Brandon in 1980 they had one son, Ryan, and another, Josh, on the way.

Now Ferguson had a clear picture for his career: He wanted to be a guidance counsellor.

That meant one more year at BU, which he started on July 2. Ferguson said they ran out of money by Christmas. A guy who’d never quit on anything wasn’t ready to start now, so he picked up a full-time physical education and English term at Crocus Plains and completed his degree with evening classes.

That meant a pot of coffee each morning before class to fuel his paper writing and studies, a full teaching day, then junior girls basketball coaching and three hours of lectures.

“And I’m not sure how we did it. My wife was a saint. She was sicker than a dog being pregnant and just hung in there while I did all my stuff … but got ‘er done,” Ferguson said. “To this day, when I look back my wife and I say ‘Why did we do this?’ The truth is if it wasn’t for her doing 90 per cent of the kid thing … we’d have fallen apart.

“I had an amazing wife who just stuck it out with me and said ‘You want to be a counsellor? All right, we can do this.’ I’m not sure if she ever regretted that statement during that year.”

He completed his program and after one year of phys. ed. and English at Earl Oxford, he started as a guidance counsellor at New Era, Harrison and Kirkcaldy Heights.

His hockey sense to defend his teammates proved important in 1984, when a group of junior high girls at Harrison told him a man in a black car outside the school was picking girls up, taking them home, drugging and sexually assaulting them during lunch hours.

Ferguson walked towards the car and made sure the man could see him take his licence plate info down. He contacted an RCMP officer he knew and passed on the info.

“He phones me back in about three minutes and says ‘Do not go near that car. That guy just got out of Stony Mountain. We’re looking at him for murder and we think he’s done some of that, we’ve got him under observation,’” Ferguson said.

“Two weeks later they bust into his place and what’s he been doing? Drugging girls at noon, videotaping, he’s got all his videotapes … I had to testify in court.”

The man was Lawrence Sowa, a dangerous sex offender who was in and out of prison before ultimately being handed a 14-year sentence in 1991. His record dates back to 1963, when he was in his early 20s, with more than 20 convictions.

“That was one of my first experiences in counselling,” Ferguson said. “At that time I wasn’t that far removed from hockey, I was OK with the physical thing so I thought ‘Well you know what? I’m going to walk over there.’ In retrospect I probably shouldn’t have … but that was an eye-opener.

“I was going mainly on instinct … I was maybe too stupid to be afraid.”

Ferguson moved over to Crocus Plains in 1990 and coached the Plainsmen hockey team from 1999 to 2007, the year that change his life in the most significant way.

OFF CAMPUS

Ferguson put together a proposal for Neelin High School Off Campus and said some folks at Brandon School Division, as well as Crocus Plains principal Barry Gooden, supported the idea. It exists today as Prairie Hope High School, an alternative school for students who dropped out or don’t fit well into the typical education system.

“I just felt the need. People were talking about it, we needed something for kids who dropped out and I just knew I wanted in on it,” Ferguson said.

So Ferguson and Brandy Hamilton set up shop at 10th Street and Rosser Avenue. They had a second-floor office space in a building crammed with furniture on the main floor. They didn’t have a phone, photocopier, or anything. And no one showed up on Day 1.

That soon changed. They had about 70 students who’d drop in for 15 minutes or a few hours a day.

“A kid would walk in and we’d talk, and these are amazing kids,” Ferguson said. “I was given second, third chances and by some people I had such kindness thrown my way that … I thought ‘These guys, they’re amazing too. They just didn’t fit in this box.’

“We had kids come in who were 19 and zero credits. Kids that as a counsellor, I had to remove from school because of a fight or they just weren’t attending, or whatever. But the neatest thing in the world was every day I’m outside the box. I get to come and when the kid walks in the door 20 minutes late, I get to say ‘Hey, good to see you.’

“For me, it didn’t get much better than that. I loved those kids and I say that with all sincerity. and I was fortunate Brandy was the same. Brandy could work so well outside the box.”

Ferguson recalled the staff team growing fairly quickly, with Brenda Cruickshank joining after about a month to help with administration, current Prairie Hope teacher Al Baker taking on math in 2008, and more eager individuals jumping onboard.

Now there are seven teachers, six student-services staffers and eight support staff members under principal Katherine MacFarlane.

Students can either graduate the regular way, with 30 credits, or by mature-student graduation. Those out of high school can come back and receive their diploma if they complete their Grade 12 courses.

Ferguson said sometimes it was just one subject a student lacked credits in, so they’d work their way up to Grade 12 then tackle the necessary work to get them through.

He could tell their stories for hours on end.

Ferguson helped a student who dropped out and worked night shifts at Maple Leaf to support his family. He’d come to Off Campus after work at 7:30 a.m., and spend an hour or two on his courses before heading to bed. He graduated.

A former hockey teammate mentioned his niece’s struggles in school, particularly English. Meanwhile, she was a published poet but simply didn’t mesh with the standard English courses. So they built a Grade 12 course around poetry.

“She aced it,” Ferguson said.

Another had zero English credits and hated school “with a passion.” She emailed Ferguson a year after he retired to check how the program was going. To Ferguson’s delight, he found out she went on to Humber College in Toronto and now works in management for an Indigenous film and media arts festival there.

Neelin Off Campus had 180 students signed up by the end of the inaugural year. That figure doubled by 2009, and the graduation totals grew as well. From 39 students in 2008 to as many as 110 in 2011, Ferguson saw more than 700 students who never thought they’d receive a high school diploma do just that.

“You should have seen our first graduation,” Ferguson said. “We did it at city hall, right in the foyer. The neatest thing, the absolute neatest thing with these guys were the parents. They’d be crying … some of them sobbing and I’d go up and give them a hug and ‘I’d never thought I’d see them graduate. Never, never.’”

They eventually had to move to McDiarmid Drive Alliance Church and would have more than 500 people in attendance. They didn’t wear robes in an effort to keep costs down but built a few small but special traditions.

“Al Baker handed out suckers,” Ferguson recalled with a grin. “That wouldn’t have meant anything to anyone except all year Al would bring suckers to kids … it was just his thing. Down they came and he’d give them a sucker and a big hug. You’d just be amazed.

“… Before we started, nobody wanted to come down. After we got going and after our first grad and all that stuff, everybody wanted to come.”

Ferguson retired in 2017 but did one more stint as a guidance counsellor, six months at Brandon’s Child and Adolescent Treatment Centre and a few other odd jobs until finally calling it quits when the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

Like many, he upped his annual golf round count and cracked 80 games for the first time this season. He’s shooting in the mid- to low-80s and trending in the right direction.

Ferguson still attends Brandon Wheat Kings games with Ryan, while Josh lives in Sylvan Lake, Alta., and has two kids, son Malcolm and daughter Lochlyn. Ferguson said Malcolm recently started playing hockey and he was able to be there to help pick out the boy’s equipment, “which was special.”

It may have taken until he was in his 50s to find his exact passion but he truly feels each step was necessary to help him influence young people the way he did and still does today.

“I remember coming home the first day and I can’t remember what it was, something didn’t work out and I said to Shelley, ‘Did I make a bad decision here?’ That was on the Friday night and by Monday morning I was all through that,” Ferguson said.

“I don’t want to sound dramatic but I knew I was called to this. I knew that this fit like … new pair of hockey gloves, which I never had.”

» tfriesen@brandonsun.com

» Twitter: @thomasmfriesen