A novel about a world on the brink

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Winnipeg Free Press subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $4.99 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

A personal resolution to read more historical fiction led me to a new novel by a renowned author. The book has great reviews, is related to my interest in the First World War and is available at the library. A bonus: the main character has a little-known connection to Brandon.

The book is “Precipice” by Robert Harris. He is a British author who has written several bestsellers. Another recent work of his, “Conclave,” was adapted into an acclaimed film.

“Precipice” is about H.H. Asquith. Largely forgotten today, Asquith was the prime minister of the United Kingdom at the beginning of the First World War. And the book is about his mistress, Venetia Stanley. She was a glamorous member of an infamous clique of British aristocrats and intellectuals known as “The Coterie.” That was in the heyday of that pampered class — before all hell broke loose in the Great War.

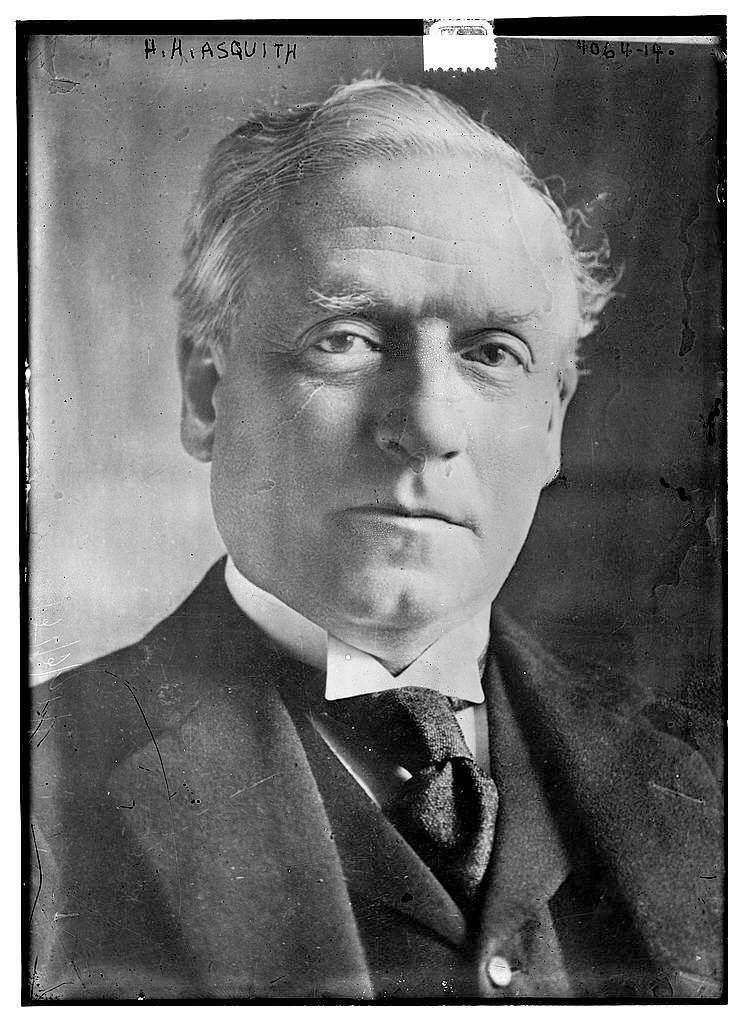

Former British prime minister H.H. Asquith is shown here sometime between 1915 and 1920. Columnist David McConkey recommends the book “Precipice,” of which Asquith is the subject, as an example of how, like many of us, world leaders are dominated by their foibles. (Library of Congress)

In 1914 London, mail was delivered 12 times a day. Writing letters back then was much like texting or emailing now. Citizens could write a letter, have it delivered and receive a reply — all in the same day. This excellent postal service was handy for an indefatigable correspondent like Asquith: the besotted fellow would send his mistress Stanley as many as three or four letters a day.

Although Asquith later destroyed her letters to him, Stanley saved his letters to her. So Asquith’s correspondence was available for Harris’s research. “The reader may be astonished to learn,” Harris explains in an author’s note before the book, that all the letters quoted in the novel are authentic.” Asquith’s letters contained not only expressions of endearment, but also top government secrets.

Decades later, another British prime minister was asked to identify the greatest challenge for any leader. “Events, dear boy,” he replied, “events.” Asquith’s fate was to be confronted by one of the biggest “events” ever: the outbreak of the First World War.

In 1914, Asquith had been prime minister for six years, accustomed to wielding power in a grinding environment of never-ending troubles. Asquith had concluded that politics was “merely a process of replacing one problem with another.”

Harris notes that Asquith’s “response, as always when faced with potential unpleasantness, personal or political, was to ignore it, in the hope it would go away, which it mostly did.” This approach served Asquith well — until it didn’t.

A question emerges from the novel: if Asquith hadn’t been preoccupied with his affair with Stanley, would world history have turned out differently? The likely answer: yes.

When important decisions were being made, the prime minister’s attention was diverted. When he should have been concentrating on affairs of state, Asquith was planning romantic getaways. When vital issues were being discussed in cabinet meetings, Asquith was furtively writing love letters.

Reality is not set in stone. Britain could have done more to prevent war in the first place. And the disastrous campaign at Gallipoli could have been prevented.

The novel brings home a critical reminder: those orchestrating world events are just folks after all. Real people, with their foibles. Some, like Asquith — who also had a drinking problem — were dominated by their foibles.

Asquith today is regarded as a failed leader who was ousted because the war was going poorly. He has been overshadowed in history by David Lloyd George, his successor as prime minister. Lloyd George is remembered as the prime minister who won the war and then played a big role at the Paris peace talks.

Perhaps “Precipice” will reignite interest in Asquith’s story. For intriguing consideration, there were his indiscretions, his drinking and how history revolves around flawed personalities.

As a postscript, what about the connection to Brandon? When Asquith retired from politics, he was given the honorary title, the Earl of Oxford. He died soon after, at age 75. That same year, 1928, a new school was built in Brandon. The school here was named after the former British prime minister.