The feminism of early Brandon resonates still

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

A vice-regal visit and a local feminist leader in Brandon’s early years provide an intriguing glimpse into our past. The visit to Brandon was by the governor general and his wife, Lord and Lady Aberdeen. During the visit, Lady Aberdeen spoke to women who wanted to start a branch of the National Council of Women. Prominent at the meeting was Jessie Turnbull McEwen.

The Aberdeens arrived by train in the afternoon of Dec. 4, 1895. They went first to 247 Russell St. to a luncheon at the elegant home of Senator John Kirchhoffer and his wife, Clara. The Aberdeens then went to the opera house, which was on the second floor of City Hall at the corner of Eighth and Princess.

The opera house, The Brandon Sun reported, “was crowded to the doors with ladies.” This gathering “must have been a gratifying sight to their Excellencies.” Lord Aberdeen addressed the audience, speaking, the Sun noted, “in his usual happy manner.” He then presented medals to school students for deportment, politeness, unselfishness and scholarship.

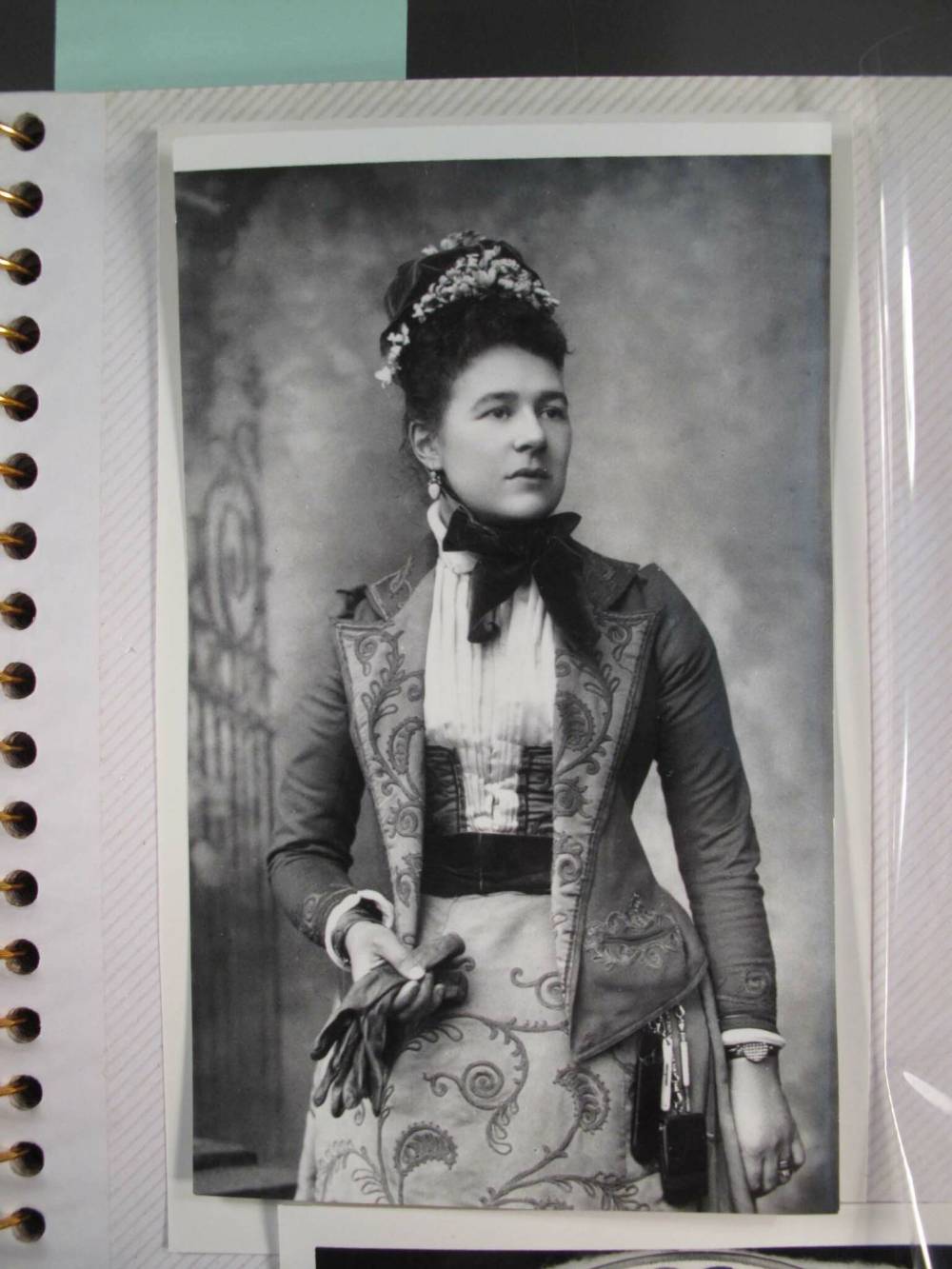

This photograph of a Manitoba Archives picture shows Lady Ishbel Aberdeen, founder of the National Council of Women in 1893. (Mike Deal/Winnipeg Free Press files)

Deportment. Politeness. Let’s stop and reflect for a moment. A decade and a half before, Brandon was a tiny settlement of tents. Now, citizens of the city assembled in the opera house, greeting the governor general and honouring personal and civic virtues.

After the governor general departed to participate in a curling match, Lady Aberdeen spoke to the assembled women.

A woman ahead of her time, Lady Aberdeen was concerned about social issues and women’s suffrage. The Aberdeens had travelled across Canada before he became governor general. Seeing the need for reading material, she set up the Lady Aberdeen Association for Distribution of Literature to Settlers in the West.

While her husband served as governor general, Lady Aberdeen overcame the resistance of male physicians to organize the Victorian Order of Nurses. She also founded the National Council of Women, encouraging the formation of local branches as the vice-regal couple traversed the country.

Lady Aberdeen was such a commanding figure that social historian Sandra Gwyn suggested that she could be regarded as Canada’s first female governor general. Lord Aberdeen, “in his usual happy manner,” could be seen as her consort.

Jessie Turnbull McEwen chaired the opera house meeting. McEwen had long been active in women’s organizations. While living in Toronto, she worked with pioneering feminists like Emily Stowe, the first female physician to practise in Canada. They set up the Toronto Women’s Literary Club, with McEwen as president.

The club successfully lobbied in 1882 for qualified single women and widows to vote in municipal elections in Ontario. Buoyed by this success, the club reorganized itself as the Canadian Women’s Suffrage Association. McEwen continued as president. This was the first such group in Canada.

McEwen’s husband Donald was a successful importer of Scottish wool. In 1884, the McEwens decided to try agriculture as well and they and their four children moved to a farm northwest of Brandon. They built a large home, where they entertained both local folks and visiting dignitaries.

After Lady Aberdeen spoke, the women voted to establish a Brandon branch of the National Council of Women. McEwen was elected president. An executive committee was formed, consisting of “all the presidents of the different ladies’ societies in Brandon.”

McEwen served as president of the Brandon branch until 1916 and also served as vice-president of the national association. Locally, the council initiated a public library and promoted the hospital, social and educational programs, as well as the election of women as school board trustees.

Small in stature, McEwen was imposing in character. “The spare frame implied frailty,” Brandon Sun columnist Kaye Rowe wrote in a 1959 tribute, “but it was the fragility of a steel girder.”

With an all-Canadian blend of politeness and toughness, McEwen was a key figure in the women’s rights movement. “While women like Nellie McClung and the Beynon sisters were the public face of the suffrage movement in Manitoba,” history writer Dale Brawn observed, McEwen “was its heart and soul.”

McEwen died in 1920 at the age of 74 and was buried in the Brandon Cemetery. Her death was reported on the front page of the Sun. “The Master Calls Mrs. Donald McEwen,” the headline read, “One of the Pioneers in Women’s Work Throughout the Great West.” The Sun remarked that McEwen’s efforts with the National Council of Women faced “much opposition.” But McEwen had “caught the broad vision of the future.”

The feminism of Brandon’s early years resonates through our history. Although the historical record is scanty, Jessie Turnbull McEwen is likely remembered by McEwen Drive and Lord and Lady Aberdeen by Aberdeen Avenue. And we can witness ongoing community engagement to secure women’s rights, dignity and safety.