Canada needs to address shortage of tech workers

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Canada is facing serious economic challenges. Our standard of living is falling and has been for years. Our biggest trading partner is slapping tariffs on our goods and throwing uncertainty into our export markets. About 1.6 million Canadians are currently unemployed, and many more are working in jobs that don’t keep pace with the rising cost of living. At the same time, businesses across sectors are struggling to find skilled staff, a problem made worse by our aging workforce.

This isn’t just a rough patch. It’s a structural crisis. And there’s only one way out: we must boost productivity — how much we produce per hour of work — because it directly affects wages, prices and our ability to afford the lives we’re working for. Real gains in productivity don’t come from speeches or slogans. They come from better tools and smarter systems — in other words, technology. But technology alone doesn’t solve problems. People do.

And not just engineers or tradespeople. Technicians and technologists, the mid-level professionals who install, operate and maintain the systems that power everything from hospitals to infrastructure, are now essential across every sector. They’re not optional. They’re the backbone of our economy.

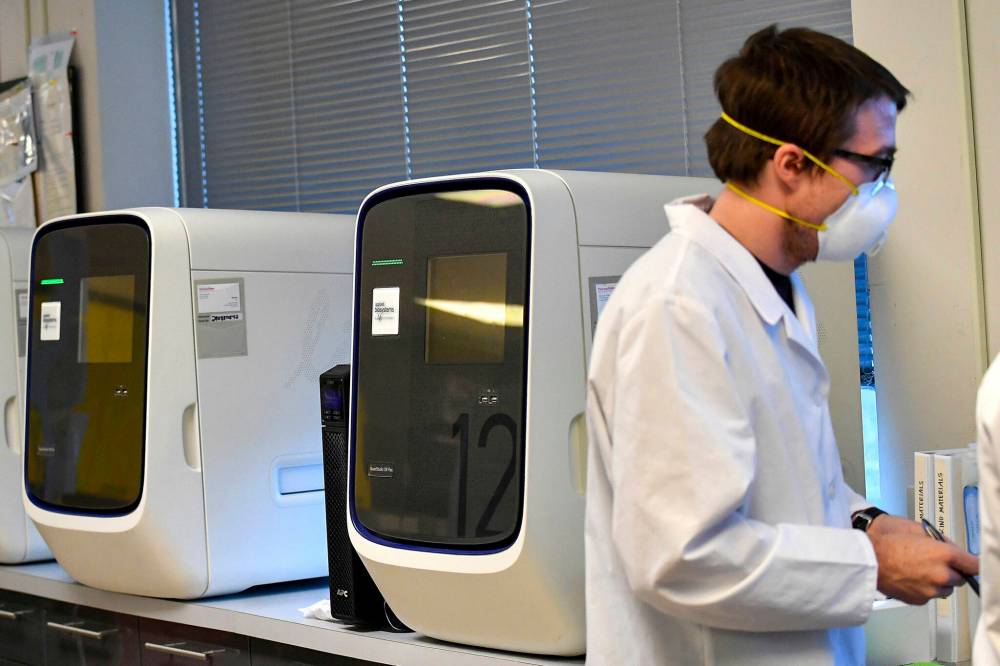

A molecular technologist works in a lab in Monroeville, Pa. Technicians and technologists, the mid-level professionals who install, operate and maintain the systems that power everything from hospitals to infrastructure, are now essential across every sector, Roslyn Kunin writes. (The Associated Press files)

We don’t have nearly enough of them.

This shortage is more than an inconvenience — it can be life-threatening. One patient in urgent need of surgery didn’t get care, not because of a lack of doctors or facilities, but because there was no anaesthesia technician available. That kind of bottleneck is playing out across health care, transportation, energy, manufacturing, construction and beyond.

Canada is in a paradox. While some workers struggle to find well-paying jobs, employers in high-demand sectors can’t fill essential positions. The missing link is targeted training and better alignment between education and labour market needs.

The idea of a separate “tech sector” is outdated. Nearly every business in Canada is now technology-dependent, whether it’s a software firm, a courier company or a fast-food chain automating orders. And without qualified people to keep these systems running, our economy slows down.

The most significant shortages, according to the Conference Board of Canada, are in computer networks, civil and electrical engineering, chemical and mechanical technology, and even geological and mineral applications. These aren’t niche specialties: they’re critical to Canada’s future. Without them, the systems that support everything from clean water to power grids to transportation don’t function properly.

So why is this talent gap still growing?

Part of the problem is awareness. Too many young people — and their parents — don’t think of these careers as first-choice options. If you’re a student or a parent helping one plan their future, take a serious look at the high demand and strong pay offered by Canada’s applied tech programs. In British Columbia, for example, the tech services sector is now a bigger economic driver than the resource sector, and tech jobs pay roughly 20 per cent more than the provincial average.

There’s also a stigma. University degrees are still seen by many as the gold standard, while two-year college programs are viewed as second-tier. But in today’s labour market, that mindset is costing us. The return on investment for many tech programs is actually higher than for some university degrees, particularly when you factor in lower tuition, faster entry into the workforce and less student debt.

Better still, most tech programs take just two years and often result in job offers before graduation. With flexible formats, including online and part-time options, they’re ideal for working adults looking to upgrade their skills and earn more.

Governments have a critical role to play. They must expand the number of tech training seats and partner with industry to fund fast, focused upskilling. That includes investing in micro-credentials — short, targeted courses that let workers update their skills as technology evolves. Just as importantly, they must actively promote these careers as essential to our economy, not second-tier alternatives.

Policymakers also need to work with employers to forecast demand more accurately. Too often, training systems are reactive. A more responsive approach would ensure that education systems are producing workers for where the economy is heading, not where it’s been.

We talk endlessly about how technology will save us from economic decline, from climate change, from global food insecurity. But the future will never arrive if we don’t have the people to build and maintain it.

Canada needs technicians and technologists.

We need them now. The future won’t wait, and neither can we.

» Roslyn Kunin is a respected Canadian economist known for her extensive work in economic forecasting, public policy and labour market analysis. She has held various prominent roles, including serving as the regional director for the federal government’s Department of Employment and Immigration in British Columbia and Yukon and as an adjunct professor at the University of British Columbia. Kunin is also recognized for her contributions to economic development, particularly in Western Canada.