Online harassment silencing Canada’s health experts

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Canada has lost the measles elimination status it has held since 1998. To regain that status, one crucial factor is hearing from researchers who speak about vaccine safety in public.

Canada can’t afford to lose expert voices at a moment when the threat of vaccine-preventable diseases is rising. Yet our work suggests that online harassment is a growing deterrent that is driving researchers and scientists out of the conversations needed at this time.

Harassment is a long-standing problem in academia. While it occurs within different institutions and disciplines, it has increasingly taken the form of online attacks from people outside of academia. It’s a phenomenon that accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and one where health experts are left to cope alone.

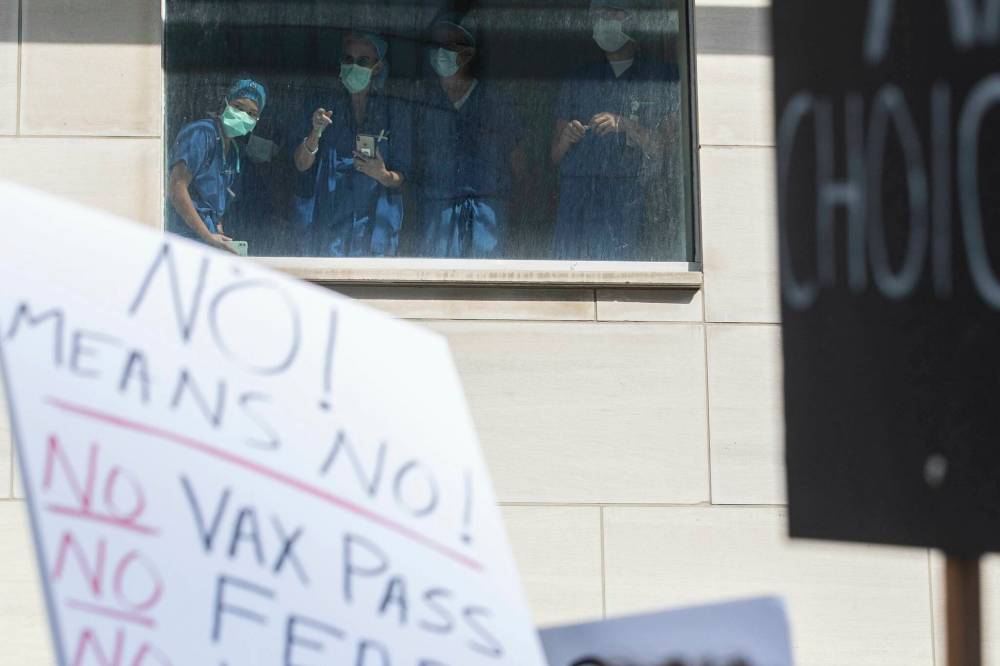

Health-care workers watch from a window as demonstrators gather outside Toronto General Hospital in September 2021 to protest against COVID-19 vaccines, COVID-19 vaccine passports and COVID-19 related restrictions. (The Canadian Press files)

Canadian institutions and research organizations need to create broad support for these individuals.

THE HARMS THAT ONLINE HARASSMENT CAN BRING

Our recent study on prominent Canadian health communicators — including university researchers and public health officials — found that 94 per cent, or 33 of 35 interviewees, had faced online abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Online harassment goes beyond vaccines and COVID-19; climate change, gender diversity, immigration and other topics have all triggered a backlash. But we found that vaccination was one of the topics most likely to trigger abuse, and it’s an issue that has become increasingly politicized in Canada.

As with many issues in Canada, developments in the United States have played a major role. For instance, a 2021 study on vaccine hesitancy in Canada showed how social media conversations on vaccinations were heavily influenced by discussions in the U.S. It turned out that Canadians followed a median of 32 Canadian accounts and 87 American accounts.

With such interconnected information ecosystems, anti-science harassment directed at American researchers routinely spills into Canadian online spaces. This is worsened when senior officials in the U.S. administration publicly express a lack of support for immunization and evidence-based health recommendations.

Canadian universities and academic institutions need to develop mitigation and support strategies to deal with online harassment fuelled by these realities.

We can learn from action plans by U.S.-based universities and coalitions. Canada can also learn from models in countries like the Netherlands that have created national initiatives to support researchers experiencing harassment.

HOSTILITY TAKES TOLL ON PUBLIC HEALTH

While academics should be comfortable having their ideas challenged, technology-facilitated harassment is very different. Online harassment is often linked with other forms of targeted abuse and includes acts of doxxing, reputation attacks or threatening and sexualized messaging, among others.

Though this hostility often targets individuals working on politically contested issues, researchers from equity-deserving groups face online abuse that builds on systemic inequities related to race, gender, sexuality and other identity factors.

Online abuse can harm mental health, provoke fears about employment or grants and undermine academic freedom, as the Canadian Association of University Teachers observes. Our research found that health communicators faced the “psychological toll” of reading hostile emails day after day, with several reporting fear, sadness or anxiety in response to threats of violence.

A racialized expert recounted how personal attacks on her appearance and background “take a toll,” while a health journalist said that messages like one wishing her “blood clots” sometimes kept her awake at night. Several interviewees described exhaustion, worry and depressive symptoms, highlighting the hidden burden of online harassment.

Besides having serious personal, institutional and societal consequences, this reality risks creating information gaps that could be quickly filled by conspiracy theories. Some health researchers decided to stop media interviews or social media posts on controversial issues. So should they simply avoid public engagement on contentious topics?

While this approach might lessen the risks, it would also dramatically reduce the impact of their expertise. Public engagement is not only a key part of research grants but it also ensures that Canadians benefit directly from research.

Currently, scholars and public health communicators targeted with online abuse mainly use individual coping strategies such as deleting social media accounts, withdrawing from public communication or accepting abuse as inevitable.

These strategies, however, leave individuals to address attacks in isolation. While such measures provide temporary relief, they reinforce self-censorship and hamper public access to expert knowledge.

THE NEED TO OFFER ‘WRAPAROUND’ SUPPORT

Institutions need to adopt “wraparound” support. This approach acknowledges researcher agency and institutional responsibility through a rights-based framework. It also shifts responsibility from individuals to institutions.

Unlike many universities’ current siloed and inflexible approach, a wraparound approach co-ordinates and integrates multiple domains of support. For instance, some targeted individuals may not face legal or safety risks but can benefit from psychological support. Others may need assistance with cybersecurity risks or removing online mentions of personal information like their home address or children’s school.

Our institution, the University of British Columbia, for example, offers cybersecurity assistance, mental health support and other key elements of a response.

However, when we consulted faculty and staff, we learned that people found it daunting to figure out all the supports available and how to access them. We created an online resource to help. York University solved that problem by creating a map.

Canadian universities can also turn to international models for inspiration. Fourteen universities in the Netherlands, for instance, participate in a joint SafeScience initiative, which offers guidance and a national helpline to report incidents. Germany’s SciComm-Support provides resources, training and free counselling to researchers.

If we expect scientists and health experts to speak out about issues like measles vaccination for the good of society, they must know that their employers and institutions will stand with them, that they will have their backs.

Canada cannot prepare for future public health emergencies, like another pandemic, without protecting the safety of researchers and their freedom to pursue their lines of inquiry without fear.

» Heidi J.S. Tworek is a professor of history and public policy at the University of British Columbia; Chris Tenove is an assistant director of the Centre for the Study of Democratic Institutions at UBC; and Netheena Neena Mathews is a UBC research assistant.

» This article first appeared on The Conversation Canada: theconversation.com/ca.