The economics of vaccination

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Most see eliminating pain and disability as the essential benefit of avoiding infectious disease, and public health officials promote vaccination as the most cost-effective way to combat flu, measles, and COVID. Public health experts often confine their perspectives on how disease affects a population solely to matters of quality of life and life extension.

With the current flu season upon us, its resurgent and mutating H3N2 strain, the new COVID-19 variant on the prowl, and Canada’s recent loss of measles elimination status, it is crucial to recognize the threats these diseases pose to Canada’s economic welfare.

Economics offers valuable perspectives on the impact of infectious disease, people’s reactions to its spread, and options for control.

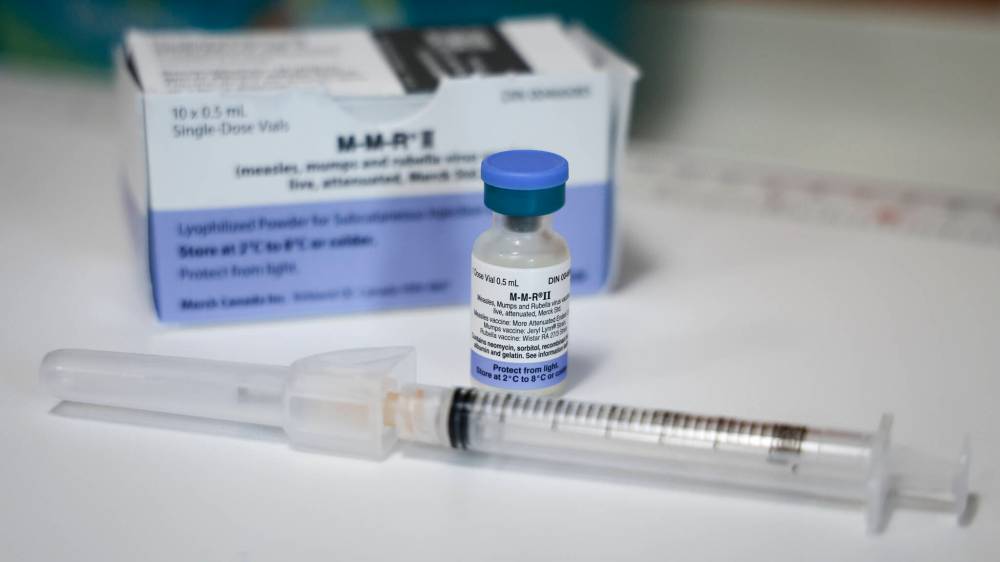

A vial of measles, mumps and rubella vaccine is pictured at the Taber Community Health Centre in Taber, Alta. on July 28. Vaccination programs aren’t just about health — they’re also about the economic impact and costs of illness, writes Gregory Mason. (The Canadian Press)

Consider how infectious disease threatens economic performance. Back when the Vietnam War was dragging the United States into fiscal quicksand, Congress needed to “defund” unnecessary spending, so it latched onto cancelling measles immunizations as offering opportunities to find money for the war.

In 1969, Axnick, Shavell, and Witte published a retrospective observational study examining the benefits and costs of measles vaccination. Their methodology used U.S. data on measles incidence before and after vaccination. A key cost benefit analysis in health care is recognizing that avoided costs are the crucial benefit, and that vaccination is all about cost avoidance. The economic costs of disease fall into three categories: direct, indirect and intangible.

Offsetting the direct costs of immunization (the cost of the measles vaccine and its delivery to the public) are three avoided costs that become essential benefits of vaccination. First, there are the lost school days due to sick children, which lead to educational delays, and the income (productivity) loss experienced by caregivers (mostly parents).

Second, there are indirect costs, including care for the small number of children who contract encephalitis, a rare but potentially serious consequence of measles.

Although only a few children will develop encephalitis, some will experience severe brain damage and become vegetative, requiring life-time care; these costs mount rapidly when calculated against the total population of a country.

Third, and most important, are the lifetime losses incurred because those few children who die deprive the economy of their contribution as working adults. Added to this is the loss to the economy of those who live but can never work.

In both cases, since children might have 35–40 years of paid work, the elimination of these lifetime incomes is the intangible cost of measles and a long-term drag on the economy.

Axnick and his colleagues found that the direct costs (in 1969 dollars) of the measles vaccination program amounted to about $108 million; however, the three benefits (avoided costs) associated with cancelling the vaccine program would trigger $531 million in lifetime productivity gains.

Congress quickly shelved any plan to cancel measles vaccination.

Research on the value of flu vaccination shows similar benefits. Recent studies estimate the costs (direct costs and productivity losses) of flu to the U.S. economy at between US$50 and US$90 billion, or around $5 billion to the Canadian economy.

Seasonal flu, RSV and COVID are critical hits to our already tepid economic productivity. Thus far in 2025, vaccination rates in Canada have lagged 2024 levels for flu, COVID-19, and MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella). This inaction stems from an information failure due to the natural inertia we all have.

It also stems from active campaigns that emphasize the adverse events experienced by the very few who receive vaccinations. A small percentage of those receiving COVID shots (mostly young men) will experience myocarditis.

The vast majority recover completely, and offsetting this cost is the much higher incidence of experiencing myocarditis from contracting COVID that the vaccine ostensibly avoids.

The term “misinformation” is overused and has become a cudgel to demonize those choosing not to vaccinate. Behavioural economics contributes to understanding vaccination decisions.

“Familiarity breeds contempt” reflects the law of diminishing marginal returns, and the concepts of habituation and reference dependence.

Someone who has been consistently vaccinated may come to value additional vaccination less each year and may lose the habit of immunization. Reference dependence occurs when memories of past pain fade, such as retching with head in toilet.

Externality is another useful economic concept that illustrates important ideas around infection and immunity.

Canada’s loss of membership in the club of countries that have eradicated measles is surely a black mark on our public health record. Measles with an R0 of between 12 and 18 means that in an unvaccinated population, one person with measles will infect, on average, 16 others, making it one of the most infectious of diseases.

A vaccine’s effectiveness is the risk reduction measured by comparing the incidence of disease in vaccinated individuals to that in unvaccinated individuals within a population. The measles vaccine has an effectiveness rate of 95 per cent, but falling vaccination rates attenuate “effectiveness rates,” as herd immunity falls, especially with highly infectious diseases such as measles.

This is why keeping measles at bay requires vaccination rates above 90 per cent. This is a classic externality: my vaccination is both a private good, benefiting me, and a public good, benefiting my neighbour.

Finally, game theory contributes insights into how human behaviour may undermine the best of vaccination programs.

Continuing with measles as the example, once vaccination rates reach 95 per cent, the remaining unvaccinated population may choose to be “free riders” since they gain herd immunity by virtue of most everyone else choosing the shot. In the second year, continued low measles incidence might prompt some who were previously vaccinated to decline vaccination, and when vaccination rates dip below 80 per cent, the downward spiral begins.

Vaccination is not just about avoiding discomfort and death.

Economics offers valuable insights into the impact of infectious diseases and into understanding how human behaviour affects immunization policies.

» Gregory Mason is an associate professor of economics at the University of Manitoba. This column was previously published in the Winnipeg Free Press.