The War From Here — Harold Daly survives Lusitania sinking

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

We need your support!

Local journalism needs your support!

As we navigate through unprecedented times, our journalists are working harder than ever to bring you the latest local updates to keep you safe and informed.

Now, more than ever, we need your support.

Starting at $15.99 plus taxes every four weeks you can access your Brandon Sun online and full access to all content as it appears on our website.

Subscribe Nowor call circulation directly at (204) 727-0527.

Your pledge helps to ensure we provide the news that matters most to your community!

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Brandon Sun access to your Free Press subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $20.00 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $24.00 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/05/2015 (3920 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

History records that on May 7, 1915, the Cunard passenger liner RMS Lusitania was torpedoed by German submarine U-20 along the coast of Ireland near Cork. The ship sank within 18 minutes. Of the 1,959 passengers and crew reported on board, 1,195 did not survive.

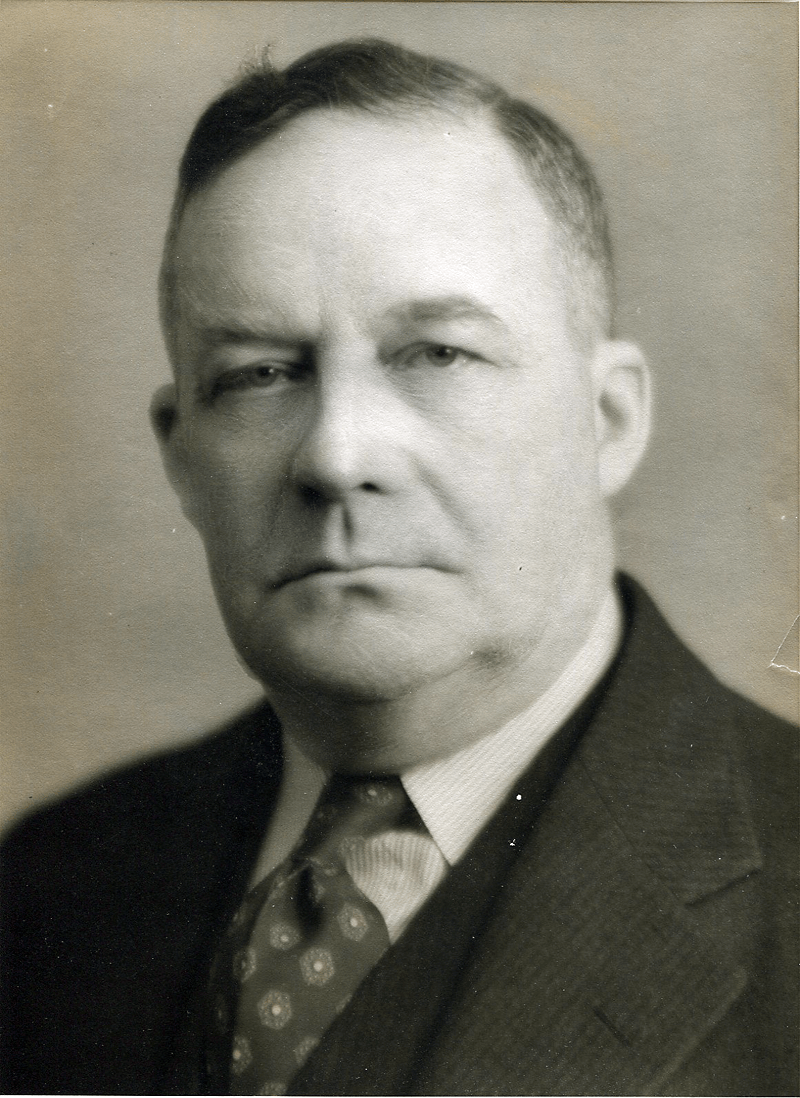

It just so happens that the son of Brandon’s first mayor, Harold Mayne Daly, was on board, and working for the federal government.

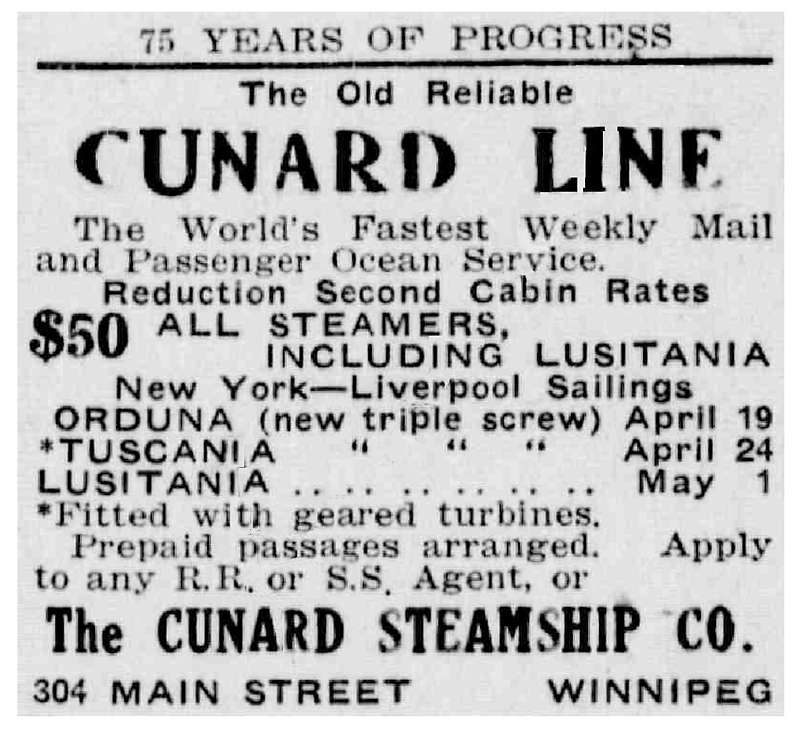

Once considered the “Greyhound of the Seas,” the Lusitania departed from New York for Liverpool on May 1, 1915, to make what became her last Atlantic crossing. The Lusitania was a superliner, built for luxury and speed. Her four turbines gave her the power needed to “win” the Blue Riband, a coveted accolade for passenger ships recording the greatest speed for transatlantic crossings. Ironically, it was the Lusitania’s speed that was said to make her invulnerable to U-boat attacks.

.png?w=1000)

The ship sank around 09:30 CDT, giving reporters time before evening headlines ran to determine if Brandonites had booked passages on the liner. Railway agents and the Cunard Steamship Company’s Main Street offices in Winnipeg were consulted. No local residents appeared to be on the Lusitania passenger lists, but there were two Brandon men who had fortuitously cancelled their reservations.

One was a Mr. Hill, who, anticipating “trouble” with immigration authorities, changed his reservation to sail on the S.S. Metagama. The other who cancelled was a Mr. Percy S. Borley, a clerk with the Canadian Phoenix Insurance Company. He owed his survival to a conflict in his schedule. He rescheduled his departure to sail on the S.S. Transylvania, another ill-fated liner, which would be torpedoed in 1917.

Harold Mayne Daly was a Lusitania passenger. The younger Daly was trained as a lawyer and dabbled as a stockbroker, working as a manager for Vancouver’s Imperial Trust Company. He had been in Ottawa, reportedly representing western firms hoping to obtain war contracts.

On May 5, 1915, however, Daly was working in another capacity: as an aide to Maj.-Gen. Sam Hughes, Canada’s Militia and Defence minister. According to historian Desmond Morton, Daly was an “all-purpose fixer.” He was sailing to England, tasked with delivering Dominion Government ballot boxes for Canadian soldiers on the front. Newspapers stated the ballots were not on board the Lusitania because the government’s printing bureau had not produced them in time for the sailing. But, two days before the ship sailed, there had been other reports. Express rigs, loaded with steel-bound chests containing ballots, were said to have departed Parliament Hill after a memorial service there. The service had been to honour the thousands of Canadians recently killed at Ypres.

According to the Lusitania Resource website, Daly was in a lounge playing solitaire minutes before the torpedo struck the ship. Deciding to purchase a cigar from the bartender, Daly heeded the man’s warning to evacuate, but was washed overboard upon exiting the lounge. Once on dry land, Daly cabled the Canadian minister of Public Works, declaring, “I am still quite willing to die for the Conservative party but am glad I didn’t drown for it.”

Daly was fortunate to have survived the frigid waters, as many of the passengers succumbed to exposure before they could be rescued. The Manitoba Free Press reported 29 passengers purchased tickets in Winnipeg for the Lusitania’s final crossing. Of those, 11 were saved, one was lost and 17 remained unaccounted.

In the week prior to the Lusitania disaster, German submarines sank nine British merchant ships and 19 fishing trawlers; U-20 was responsible for three of those vessels. After U-20 fired its torpedo at the Lusitania, the commander noted in his log an “unusually heavy detonation” accompanied by a “very strong explosive cloud.” He speculated a secondary explosion must have followed, causing the liner to dramatically list starboard and immerse at the bow. Passengers aboard the Lusitania confirmed feeling or hearing another explosion seconds after the torpedo hit. This second explosion has been the focus of much speculation, conspiracy theory and debate for the past century.

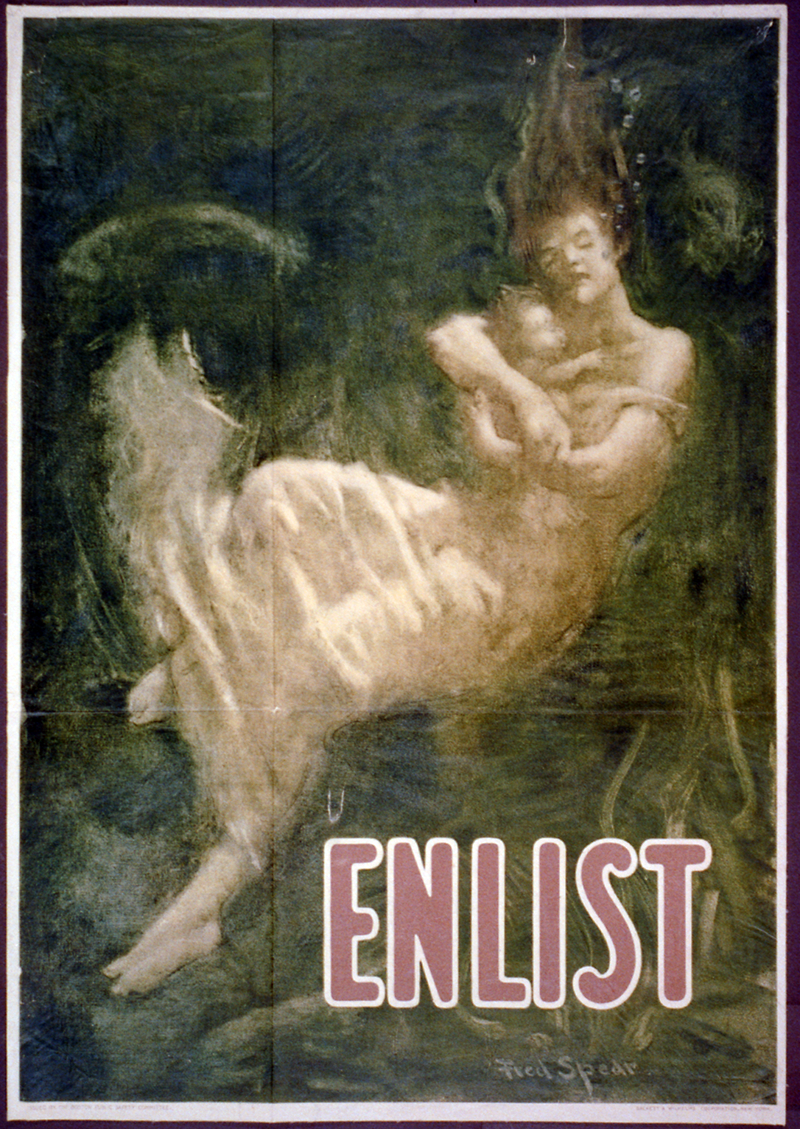

The sinking of the Lusitania became a powerful propaganda tool for both the Germans and the Allies. Following the attack, Germany faced worldwide condemnation. Germany counter-argued that Britain was secretly transporting high explosives. These, not the single torpedo, caused the catastrophic explosion that sank the ship. Furthermore, rumours circulated that Canadian troops were being transported by the Lusitania. According to the rules of war, the liner was a legitimate target if she transported “war materials” or soldiers.

At the time, the Canadian government did not want to lend credence to the Canadian troop rumour. Yet it was faced with a potential problem, if not an embarrassment: a survivor named “Captain” Harold Mayne Daly.

In 1915, Canada had no legal authority over her troops once they were part of the British Army. Thus, Prime Minister Robert Borden had to seek permission from the British government for the soldiers’ vote. The British government cabled its approval on May 5, 1915. A hastily drawn-up attestation paper for Daly identifies him as an officer at headquarters, dated that same day. Daly, however, was already aboard the Lusitania with the soldiers’ ballots. Officials decided the reason for Daly’s trip to England would be classified as a military secret, and newsmen were fed the story the ballots never made it aboard the ship. The U-20, however, had scuttled the soldiers’ vote, both literally and figuratively.

Today — 100 years after its sinking — the wreck of the Lusitania rests on her starboard side, 100 metres below the Celtic Sea. American entrepreneur Gregg Bemis and partners purchased the wreck from the Liverpool and London War Risks Insurance Association in the 1960s. During the 1990s, the Irish government placed an underwater heritage order on the Lusitania, declaring her a protected site; all luggage and cargo belong to Irish authorities. Regulated diving expeditions have revealed caches of .303 Remington cartridges on the wreck, but not the Canadians’ ballot boxes. Regardless of ownership, the RMS Lusitania remains an underwater tomb for the nearly 900 souls who were lost at sea.

» Suyoko Tsukamoto is a Brandonite that has spent three seasons in the archaeology field at Camp Hughes National Historic site. warfromhere@gmail.com